Archive

DataLoggerThread

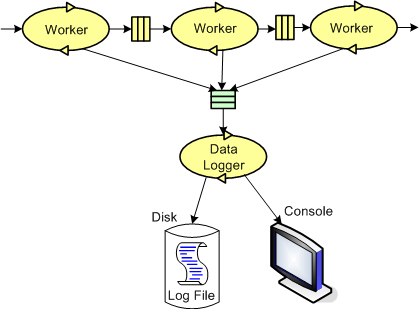

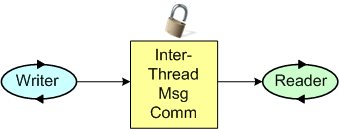

The figure below models a program in which a pipeline of worker threads communicate with each other via message passing. The accordion thingies ‘tween the threads are message queues that keep the threads loosely coupled and prevent message bursts from overwhelming downstream threads.

During the process of writing one of these multi-threaded programs to handle bursty, high rate, message streams, I needed a way to periodically extract state information from each thread so that I could “see” and evaluate what the hell was happening inside the system during runtime. Thus, I wrote a generic “Data Logger” thread and added periodic state reporting functionality to each worker thread to round out the system:

Because the reporting frequency is low (it’s configurable for each worker thread and the default value is once every 5 seconds) and the state report messages are small, I didn’t feel the need to provide a queue per worker thread – YAGNI.

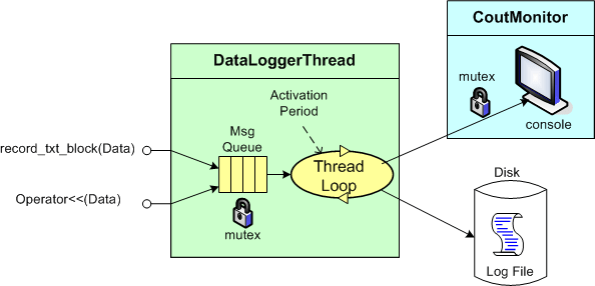

The figure below shows a more detailed design model of the data logging facility in the form of a “bent” UML class diagram. Upon construction, each DataLoggerThread object can be configured to output state messages to a user named disk file and/or the global console during runtime. The rate at which a DataLoggerThread object “pops” state report messages from its input queue is also configurable.

The DataLoggerThread class provides two different methods of access to user code at runtime:

void DataLoggerThread::record_txt_block(const Data&)

and

void DataLoggerThread::operator<<(const Data&).

Objects of the DataLoggerThread class run in their own thread of execution – transparently in the background to mainline user code. On construction, each object instance creates a mutex-protected, inter-thread queue and auto-starts its own thread of operation behind the scenes. On destruction, the object gracefully self-terminates. During runtime, each DataLoggerThread object polls its input queue and formats/writes the queue entries to the global console (which is protected from simultaneous, multiple thread access by a previously developed CoutMonitor class) and/or to a user-named disk log file. The queue is drained of all entries on each (configurable,) periodic activation by the underlying (Boost) threads library.

DataLoggerThread objects pre-pend a “milliseconds since midnight” timestamp to each log entry just prior to being pushed onto the queue and a date-time stamp is pre-pended to each user supplied filespec so that file access collisions don’t occur between multiple instances of the class.

That’s all I’m gonna disclose for now, but that’s OK because every programmer who writes soft, real-time, multi-threaded code has their own homegrown contraption, no?

My Erlang Learning Status – IV

I haven’t progressed forward at all on my previously stated goal of learning how to program idiomatically in Erlang. I’m still at the same point in the two books (“Erlang And OTP In Action“; “Erlang Programming“) that I’m using to learn the language and I’m finding it hard to pick them up and move forward.

I’m still a big fan (from afar) of Erlang and the Erlang community, but my initial excitement over discovering this terrific language has waned quite a bit. I think it’s because:

- I work in C++ everyday

- C++11 is upon us and learning it has moved up to number 1 on my priority list.

- There are no Erlang projects in progress or in the planning stages where I work. Most people don’t even know the language exists.

Because of the excuses, uh, reasons above, I’ve lowered my expectations. I’ve changed my goal from “learning to program idiomatically” in Erlang to finishing reading the two terrific books that I have at my disposal.

Note: If you’re interested in reading my previous Erlang learning status reports, here are the links:

Centralized, Federated, Decentralized

1 Prelude

A colleague on LinkedIn.com pointed me toward this Doug Schmidt, et al, paper: “Evaluating Technologies for Tactical Information Management in Net-Centric Systems“. In it, Doug and crew qualitatively (scalability, availability, configurability) and quantitatively (latency, jitter) evaluate three different architectural implementations of the Object Management Group‘s (OMG) Data Distribution Service (DDS): centralized, federated, and decentralized.

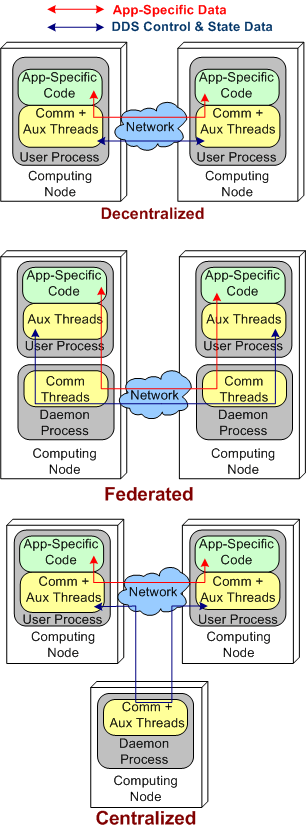

The stacked trio of figures below model the three DDS architecture types. They’re slightly enhanced renderings of the sketches in the paper.

2 Quantitative Comparisons

DDS was specifically designed to meet the demanding latency and jitter (the standard deviation of latency) performance attributes that are characteristic of streaming, Distributed Real-Time Event (DRE) systems like defense and air traffic control radars. Unlike most client-server, request-response systems, if data required for human or computer decision-making is not made available in a timely fashion, people could die. It’s as simple and potentially horrible as that.

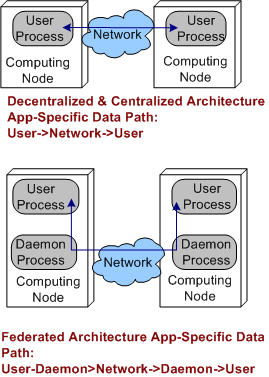

Applying the systems thinking idiom of “purposeful, selective ignorance“, the pics below abstract away the unimportant details of the pics above so that the architecture types can be compared in terms of latency and jitter performance.

By inspecting the figures, it’s a no brainer, right? The steady-state latency and jitter performance of the decentralized and centralized architectures should exceed that of the federated architecture. There is no “middleman“, a daemon, for application layer data messages to pass through.

Sure enough, on their two node test fixture (I don’t know why they even bothered with the one node fixture since that really isn’t a “distributed” system in my mind) , the Schmidt et al measurements indicate that the latency/jitter performance of the decentralized and centralized architectures exceed that of the federated architecture. The performance difference that they measured was on the order of 2X.

3 Qualitative Comparisons

In all distributed systems, both DRE and Client-Server types, achieving high operational availability is a huge challenge. Hell, when the system goes bust, fuggedaboud the timeliness of the data, no freakin’ work can get done and panic can and usually does set in. D’oh!

With that scary aspect in mind, let’s look at each of the three architectures in terms of their ability to withstand faults.

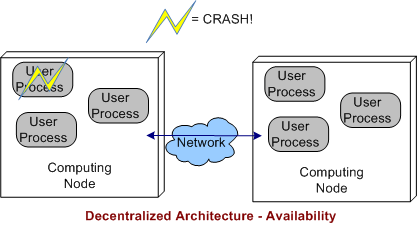

3.1 Decentralized Architecture Availability

In a decentralized architecture, there are no invasive daemons that “leak” into the application plane so we can’t talk about daemon crashes. Thus, right off the bat we can “arguably” say that a decentralized architecture is more resistant to faults than the federated or centralized architectures.

As the picture below shows, when a user application layer process dies, the others can continue to communicate with each other. Depending on what the specific application is required to do during operation, at least some work may be able to still get accomplished even though one or more app components go kaput.

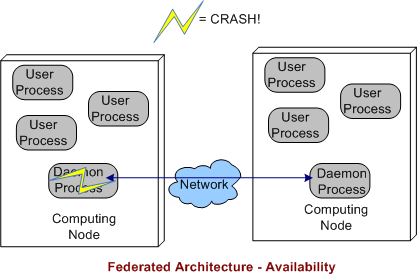

3.2 Federated Architecture Availability

In a federated architecture, when a daemon process dies, a whole node and all the subscriber application user processes running on it are severed from communicating with the user processes running on the other nodes (see the sketch below) in the system. Thus, the federated architecture is “arguably” less fault tolerant than the decentralized and (as we’ll see) centralized architectures. However, through judicious “allocation” of user processes to nodes (the fewer the better – which sort of defeats the purpose of choosing a federation for per node intra-communication performance optimization), some work still may be able to get accomplished when a node’s daemon crashes.

If the node daemons stay viable but a user application dies, then the behavior of a federated architecture, DDS-based system is the same as that of a decentralized architecture

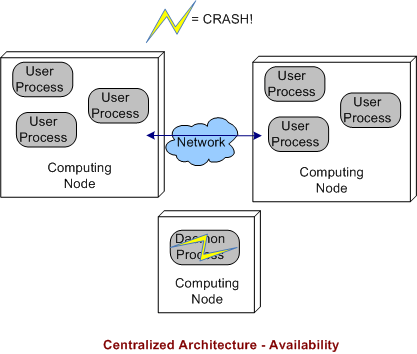

3.3 Centralized Architecture Availability

Finally, we come to the robustness of a centralized DDS architecture. As shown below, since the single daemon overlord in the system is not (or should not be) involved in inter-process application layer data communications, if it crashes, then the system can continue to do its full workload. When a user process crashes instead of, or in addition to, the daemon, then the system’s behavior is the same as a decentralized architecture.

4 BD00 Commentary

Because he works on data streaming DRE radar systems, Jimmy likes, I mean BD00 likes, the DDS pub-sub architectural style over broker-based, distributed communication technologies like C/S CORBA and JMS queues. It should be obvious that the latter technologies are not a good match for high availability and low latency DRE applications. Thus, trying to jam fit a new DRE application into a CORBA or JMS communication platform “just because we have one” is a dumb-ass thing to do and is sure to lead to high downstream maintenance costs and a quicker route to archeosclerosis.

Within the DDS space, BD00 prefers the decentralized architecture over the federated and centralized styles because of the semi-objective conclusions arrived at and documented in this post.

Using The New C++ DDS API

PrismTech‘s Angelo Corsaro is a passionate and tireless promoter of the OMG’s Data Distribution Service (DDS) distributed system communication middleware technology. (IMHO, the real power of DDS over other messaging services and messaging-based languages like Erlang (which I love) is the rich set of Quality of Service (QoS) settings it supports). In his terrific “The Present and Future of DDS” pitch, Angelo introduces the new, more streamlined, C++ and Java DDS APIs.

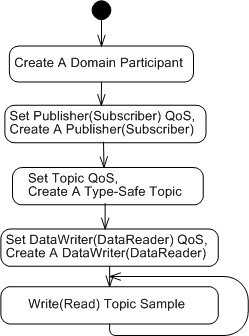

The UML activity diagram below illustrates the steps for setting up and sending (receiving) topic samples over DDS: define a domain; create a domain participant; create a QoS configured, domain-resident publisher (or subscriber); create a QoS configured and type-safe topic; create a QoS configured, publisher-resident, and topic-specific dataWriter; and then go!

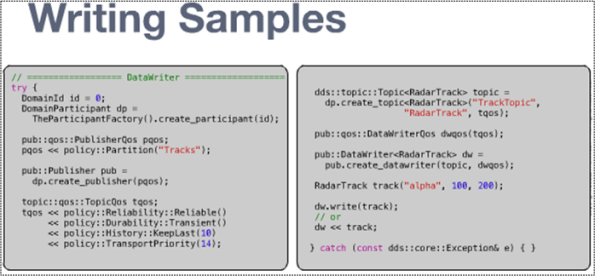

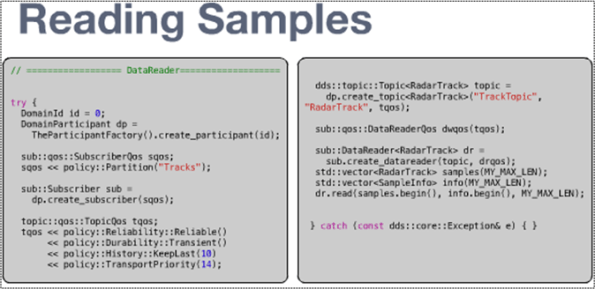

Concrete C++ implementations of the activity diagram, snipped from Angelo’s presentation, are presented below. Note the incorporation of overloaded insertion operators and class templates in the new API. Relatively short and sweet, no?

Even though the sample code shows non-blocking, synchronous send/receive usage, DDS, like any other communication service worth its salt, provides API support for blocked synchronous and asynchronous notification usage.

So, what are you waiting for? Skidaddle over to PrismTech’s OpenSplice DDS page, download the community edition libraries for your platform, and start experimenting!

My Erlang Learning Status – III

Since my last status report, I haven’t done much studying or code-writing with Erlang. It’s not because I don’t want to, it’s just that learning a new programming language well enough to write idiomatic code in it is a huge time sink (for me) and there’s just not enough time to “allocate” to the things I want to pursue.

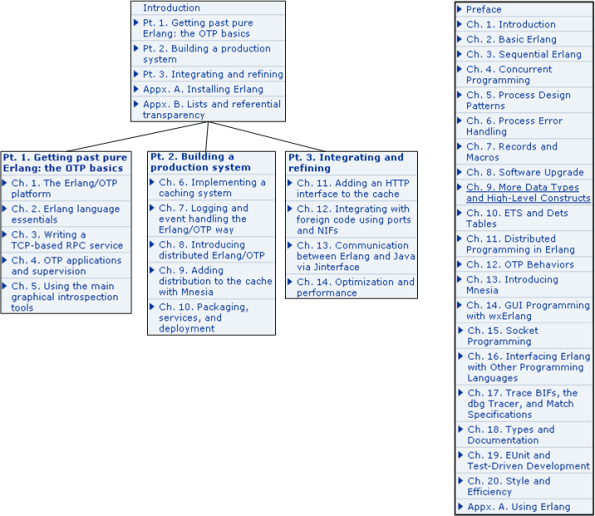

However, that may change now that I have e-access (through my safaribooksonline.com subscription) to a second, terrific, Erlang book: “Erlang And OTP In Action“. Together with the equi-terrific book, “Erlang Programming“, the two different teaching approaches are just what may motivate me to pick up the pace.

When learning a new topic, I like to use multiple sources of authority so that I can learn the subject matter from different points of view. It’s interesting to compare the table of contents for the two books:

Currently, I’m in chapter 2 of the Erlang/OTP book (left TOC above) and chapter 6 in the Erlang book. As I lurch forward, the going gets slooower because the concepts and language features are getting more advanced. I hate when that happens. 🙂

Note: If you’re interested in reading my first Erlang learning status report, click here. My second one is here.

SysML, UML, MML

I really like the SysML and UML for modeling and reasoning about complex, multi-technology and software-centric systems respectively, but I think they have one glaring shortcoming. They aren’t very good at modeling distributed, multi-process, multi-threaded systems. Why? Because every major element (except for a use case?) is represented as a rectangle. As far as I know, a process can be modeled as either a parallelogram or a stereotyped rectangular UML class (SysML block ):

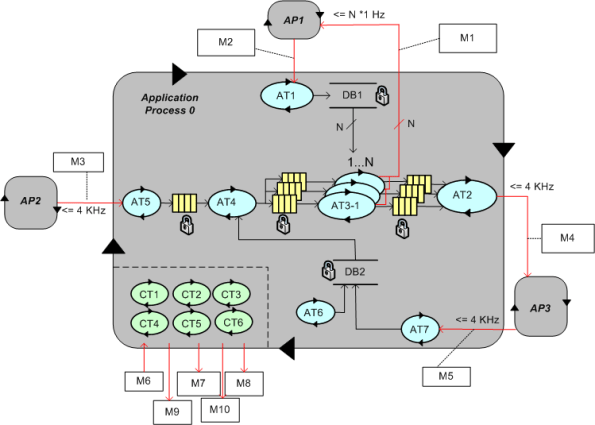

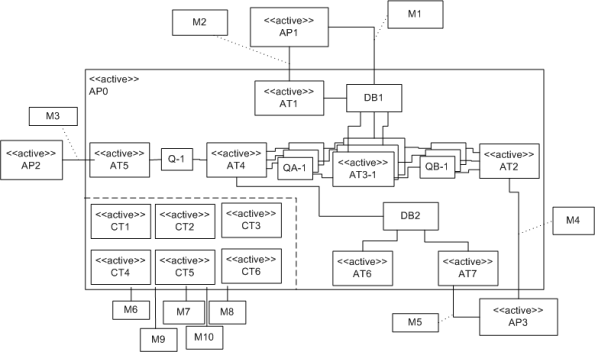

To better communicate an understanding of multi-threaded, multi-process systems, I’ve created my own graphical “proprietary” (a.k.a. homegrown) symbology. I call it the MML (UML profile). Here is the MML symbol set.

An example MML diagram of a design that I’m working on is shown below. The app-specific modeling element names have been given un-descriptive names like ATx, APx, DBx, Mx for obvious reasons.

Compare this model with the equivalent rectangular UML diagram below. I purposely didn’t use color and made sure it was bland so that you’d answer the following question the way I want you to. Which do you think is more expressive and makes for a better communication and reasoning tool?

If you said “the UML diagram is better“, that’s OK. 🙂

My Erlang Learning Status – II

In my quest to learn the Erlang programming language, I’ve been sloowly making my way through Cesarini and Thompson’s wonderful book: “Erlang Programming“.

In terms of the book’s table of contents, I’ve just finished reading Chapter 4 (twice):

As I expected, programming concurrent software systems in Erlang is stunningly elegant compared to the language I currently love and use, C++. In comparison to C++ and (AFAIK) all the other popularly used programming languages, concurrency was designed into the language from day one. Thus, the amount of code one needs to write to get a program comprised of communicating processes up and running is breathtakingly small.

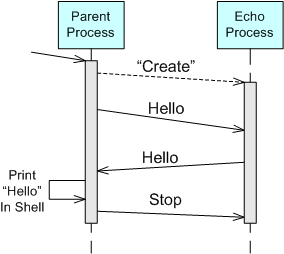

For example, take a look at the “bent” UML sequence diagram of the simple two process “echo” program below. When the parent process is launched by the user, it spawns an “Echo” process. The parent process then asynchronously sends a “Hello” message to the “Echo” process and suspends until it receives a copy of the “Hello” message back from the “Echo” process. Finally, the parent process prints “Hello” in the shell, sends a “Stop” message to the “Echo” process, and self-terminates. Of course, upon receiving the “Stop” message, the “Echo” process is required to self-terminate too.

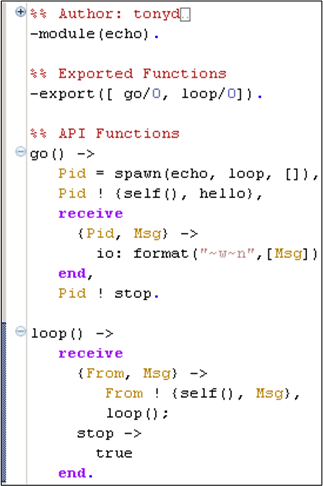

Here’s an Erlang program module from the book that implements the model:

The go() function serves as the “Parent” process and the loop() function maps to the “Echo” process in the UML sequence diagram. When the parent is launched by typing “echo:go().” into the Erlang runtime shell, it should:

- Spawn a new process that executes the loop() function that co-resides in the echo module file with the go() function.

- Send the “Hello” message to the “Echo” process (identified by the process ID bound to the “Pid” variable during the return from the spawn() function call) in the form of a tuple containing the parent’s process ID (returned from the call to self()) and the “hello” atom.

- Suspend (in the receive-end clause) until it receives a message from the “Echo” process.

- Print out the content of the received “Msg” to the console (via the io:format/2 function).

- Issue a “Stop” message to the “Echo” process in the form of the “stop” atom.

- Self-terminate (returning control and the “stop” atom to the shell after the Pid ! stop. expression).

When the loop() function executes, it should:

Suspend in the receive-end clause until it receives a message in the form of either: A) a two argument tuple – from any other running process, or, B) an atom labeled “stop“.

- If the received message is of type A), send a copy of the received Msg tuple argument back to the process whose ID was bound to the From variable upon message reception. In addition to the content of the Msg variable, the transmitted message will contain the loop() process ID returned from the call to self(). After sending the tuple, suspend again and wait for the next message (via the recursive call to loop()).

- If the received message is of type B), self-terminate.

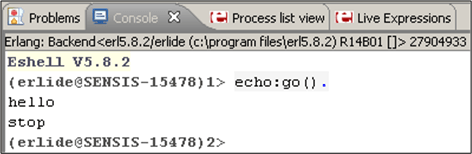

I typed this tiny program into the Eclipse Erlide plugin editor:

After I compiled the code, started the Erlang VM in the Eclipse console view, and ran the program, here’s what I got:

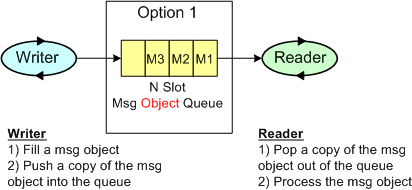

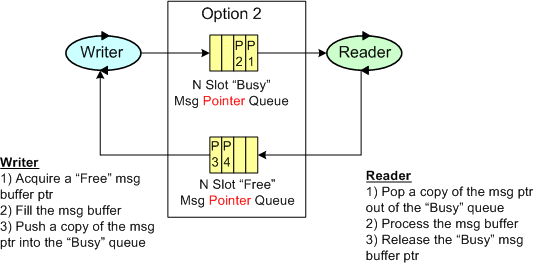

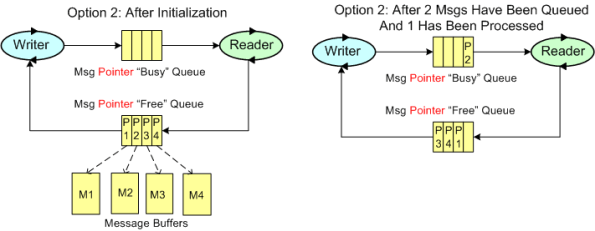

It worked like a charm – Whoo Hoo! Now, imagine what an equivalent, two process, C++ program would look like. For starters, one would have to write, compile, and run two executables that communicate via sockets or some other form of relatively arcane inter-process OS mechanism (pipe, shared memory, etc), no? For a two thread, single process C++ equivalent, a threads library must be used with some form of synchronized inter-thread communication (2 lockless ring buffers, 2 mutex protected FIFO queues, etc).

Note: If you’re interested in reading my first Erlang learning status report, click here.

Tasks, Threads, And Processes

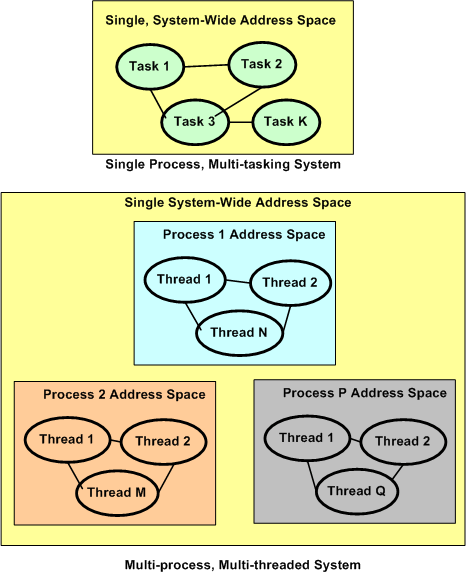

Tasks, threads, and processes. What’s the difference between them? Most, if not all Real-Time Operating Systems (RTOS) are intended to run stand-alone applications that require small memory footprints and low latency responsiveness to external events. They’re designed around the concept of a single, unified, system-wide memory address space that is shared among a set of prioritized application “tasks” that execute under the control of the RTOS. Context switching between tasks is fast in that no Memory Management Unit (MMU) hardware control registers need to be saved and retrieved to implement each switch. The trade-off for this increased speed is that when a single task crashes (divide by zero, or bus error, or illegal instruction, anyone?), the whole application gets hosed. It’s reboot city.

Modern desktop and server operating systems are intended for running multiple, totally independent, applications for multiple users. Thus, they divide the system memory space into separate “process” spaces so that when one process crashes, the remaining processes are unaffected. Hardware support in the form of an MMU is required to pull off process isolation and independence. The trade-off for this increased reliability is slower context switching times and responsiveness.

The figure below graphically summarizes what the text descriptions above have attempted to communicate. All modern, multi-process operating systems (e.g. Linux, Unix, Solaris, Windows) also support multi-threading within a process. A thread is the equivalent of an RTOS task in that if a thread crashes, the application process within which it is running can come tumbling down. Threads provide the option for increased modularity and separation of concerns within a process at the expense of another layer of context switching (beyond the layer of process-to-process context switching) and further decreased responsiveness.