Archive

Unavailability II

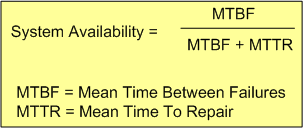

The availability of a software-intensive, electro-mechanical system can be expressed in equation form as:

With the complexity of modern day (and future) systems growing exponentially, calculating and measuring the MTBF of an aggregate of hardware and (especially) software components is virtually impossible.

Theoretically, the MTBF for an aggregate of hardware parts can be predicted if the MTBF of each individual part and how the parts are wired together, are “known“. However, the derivation becomes untenable as the number of parts skyrockets. On the software side, it’s patently impossible to predict, via mathematical derivation, the MTBF of each “part“. Who knows how many bugs are ready to rear their fugly heads during runtime?

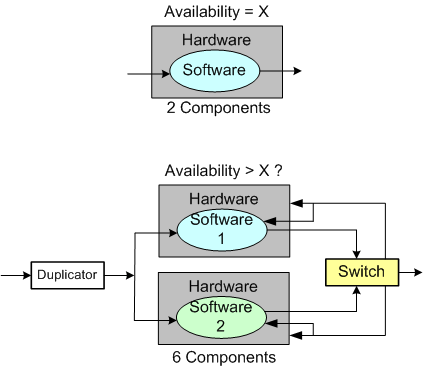

From the availability equation, it can be seen that as MTTR goes to zero, system availability goes to 100%. Thus, minimizing the MTTR, which can be measured relatively easily compared to the MTBF ogre, is one effective strategy for increasing system availability.

The “Time To Repair” is simply equal to the “Time To Detect A Failure” + “The Time To Recover From The Failure“. But to detect a failure, some sort of “smart” monitoring device (with its own MTBF value) must be added to the system – increasing the system’s complexity further. By smart, I mean that it has to have built-in knowledge of what all the system-specific failure states are. It also has to continually sample system internals and externals in order to evaluate whether the system has entered one of those failures states. Lastly, upon detection of a failure, it has to either inform an external agent (like a human being) of the failure, or somehow automatically repair the failure itself by quickly switching in a “good” redundant part(s) for the failed part(s). Piece of cake, no?

Background Daemons

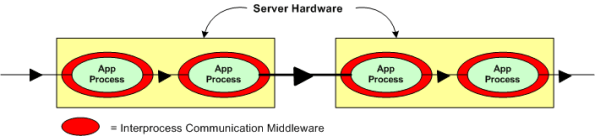

Assume that you have to build a distributed real-time system where your continuously communicating application components must run 24×7 on multiple processor nodes netted together over a local area network. In order to save development time and shield your programmers from the arcane coding details of setting up and monitoring many inter-component communication channels, you decide to investigate pre-written communication packages for inclusion into your product. After all, why would you want your programmers wasting company dollars developing non-application layer software that experts with decades of battle-hardened experience have already created?

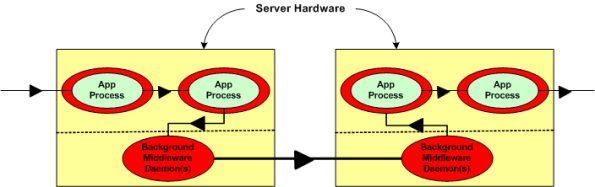

Now, assume that the figure below represents a two node portion of your many-node product where a distributed architecture middleware package has been linked (statically or dynamically) into each of your application components. By distributed architecture, I mean that the middleware doesn’t require any single point-of-failure daemons running in the background on each node.

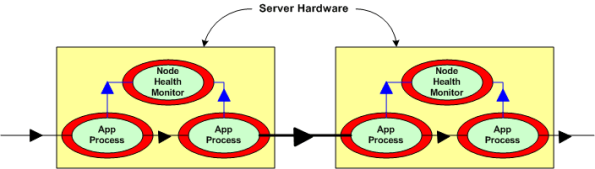

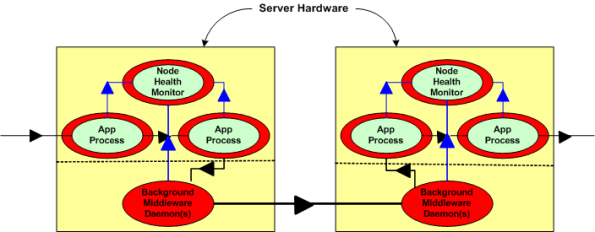

Next, assume that to increase reliability, your system design requires an application layer health monitor component running on each node as in the figure below. Since there are no daemons in the middleware architecture that can crash a node even when all the application components on that node are running flawlessly, the overall system architecture is more reliable than a daemon-based one; dontcha think? In both distributed and daemon-based architectures, a single application process crash may or may not bring down the system; the effect of failure is application-specific and not related to the middleware architecture.

The two figures below represent a daemon-based alternative to the truly distributed design previously discussed. Note the added latency in the communication path between nodes introduced by the required insertion of two daemons between the application layer communication endpoints. Also note in the second figure that each “Node Health Monitor” now has to include “daemon aware” functionality that monitors daemon state in addition to the co-resident application components. All other things being equal (which they rarely are), which architecture would you choose for a system with high availability and low latency requirements? Can you see any benefits of choosing the daemon-based middleware package over a truly distributed alternative?

The most reliable part in a system is the one that is not there – because it isn’t needed.