Me, The Banker, And You

Me, the banker, and you, before Bitcoin:

Me and you, after Bitcoin:

People who have experimented with Bitcoin can relate to this cartoon. People who haven’t, can’t; it’s simply too alien for them.

And yes, that pic on the “right” is intended to represent you, Phil 🙂

The Problem, The Culprits, The Hope

The Problem

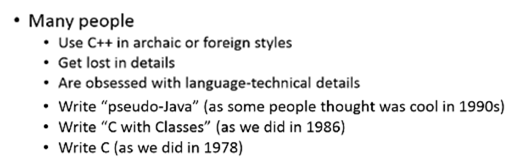

Bjarne Stroustrup’s keynote speech at CppCon 2015 was all about writing good C++11/14 code. Although “modern” C++ compilers have been in wide circulation for four years, Bjarne still sees:

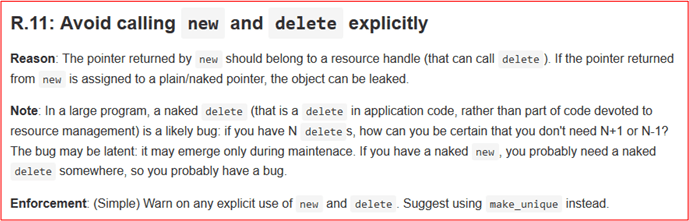

I’m not an elite, C++ committee-worthy, programmer, but I can relate to Bjarne’s frustration. Some time ago, I stumbled upon this code during a code review:

class Thing{};

std::vector<Thing> things{};

const int NUM_THINGS{2000};

for(int i=0; i<NUM_THINGS; ++i)

things.push_back(*(new Thing{}));

Upon seeing the naked “new“, I searched for a matching loop of “delete“s. Since I did not find one, I ran valgrind on the executable. Sure enough, valgrind found the memory leak. I flagged the code as having a memory leak and suggested this as a less error-prone substitution:

class Thing{};

std::vector<Thing> things{};

const int NUM_THINGS{2000};

for(int i=0; i<NUM_THINGS; ++i)

things.push_back(Thing{});

Another programmer suggested an even better, loopless, alternative:

class Thing{};

std::vector<Thing> things{};

const int NUM_THINGS{2000};

things.resize(NUM_THINGS);

Sadly, the author blew off the suggestions and said that he would add the loop of “delete“s to plug the memory leak.

The Culprits

A key culprit in keeping the nasty list of bad programming habits alive and kicking is that…

Confused, backwards-looking teaching is (still) a big problem – Bjarne Stroustrup

Perhaps an even more powerful force keeping the status quo in place is that some (many?) companies simply don’t invest in their employees. In the name of fierce competition and the never-ending quest to increase productivity (while keeping wages flat so that executive bonuses can be doled out for meeting arbitrary numbers), these 20th-century-thinking dinosaurs micro-manage their employees into cranking out code 8+ hours a day while expecting the workforce to improve on their own time.

The Hope

In an attempt to sincerely help the C++ community of over 4M programmers overcome these deeply ingrained, unsafe programming habits, Mr. Stroustrup’s whole talk was about introducing and explaining the “CPP Core Guidelines” (CGC) document and the “Guidelines Support Library” (GSL). In a powerful one-two punch, Herb Sutter followed up the next day with another keynote focused on the CGC/GSL.

The CGC is an open source repository currently available on GitHub. And as with all open source projects, it is a work in progress. The guidelines were hoisted onto GitHub to kickstart the transformation from obsolete to modern programming.

The guidelines are focused on relatively higher-level issues, such as interfaces, resource management, memory management, and concurrency. Such rules affect application architecture and library design. Following the rules will lead to code that is statically type safe, has no resource leaks, and catches many more programming logic errors than is common in code today. And it will run fast – you can afford to do things right. We are less concerned with low-level issues, such as naming conventions and indentation style. However, no topic that can help a programmer is out of bounds.

It’s a noble and great goal that Bjarne et al are striving for, but as the old saying goes, “you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink“. In the worst case, the water is there for the taking, but you can’t even find anyone to lead the horse to the oasis. Nevertheless, with the introduction of the CGC, we at least have a puddle of water in place. Over time, the open source community will grow this puddle into a lake.

A Daunting List

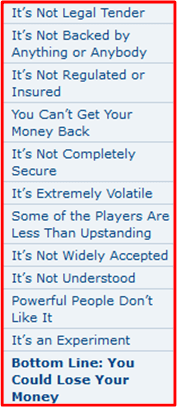

In “The Ultimate Guide to Bitcoin“, Michael Miller provides us with a daunting list of the risks associated with Bitcoin:

For BD00, the biggest existential risk on the list is “Powerful People Don’t Like It“. It’s also one of the top reasons he is into Bitcoin for the long haul. How about you?

The One Million Dollar Pizza

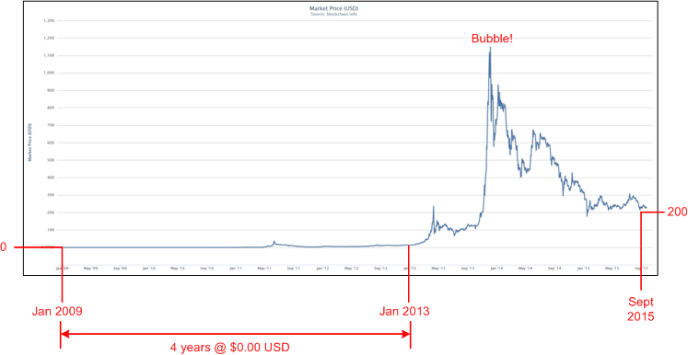

The following chart traces the Bitcoin price in USD since the system was first placed into operation in 2009.

For approximately four years, each Bitcoin was worth close to $0.00 USD. The very first exchange of Bitcoins for goods occurred in 2010. It was 10,000 BTC for two pizzas worth approximately $25 USD. At $200+ USD/BTC today, those pizzas would cost $1M each!

Imagine all those early experimenters who purchased or mined Bitcoins during the 2009-2013 time span – and then deleted their wallets from their PCs because they concluded that Bitcoin was a passing fad. I’m glad I’m not one of them. On the other side of the “coin“, I’m also glad that I didn’t jump into the market during the peak of the bubble in late 2013 at $1100 USD/BTC.

After entering the market this year at $230 USD/BTC, I wonder how I’ll feel about that decision in 5 years…..

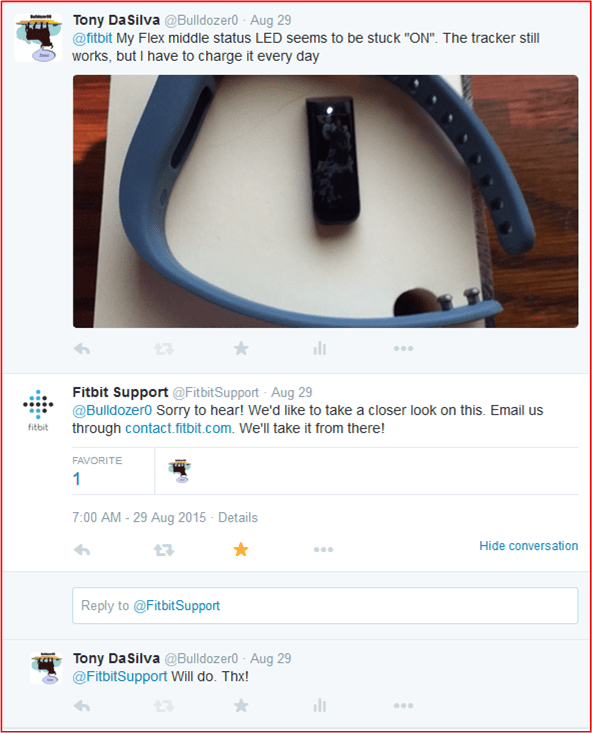

Stuck On

My Fitbit Flex has served me well for over 3+ years. However, it’s time to replace it. A hardware fault has mysteriously manifested in the form of the middle status LED switch being stuck in the “ON” position all the time:

Every time I look at it, it appears to be giving me the middle finger. LOL.

Interestingly, the step-tracking functionality still works fine. The downside is that instead of having to charge the device every 5 days, the battery discharges so fast that I don’t get an auto-generated e-mail notifying me of the low charge status. I have to remember to charge it every 2 days. Bummer.

I wanted to tell the Fitbit folks about the fault just in case they hadn’t seen this particular fault before and because the info might help them preclude it from happening again in the future, but there seems to be no way to directly relay the information to them. I browsed through their web site for 5 minutes trying to find a way to e-mail them, but I gave up in frustration. I finally ended up tweeting the picture to @fitbit.

I e-mailed Fitbit just as @fitbit suggested, but I didn’t hear anything back from them. Nada, zilch.

Perhaps FitBit should be more Zappos-like; obsessed with customer service. As you can see below, the zappos.com front page prominently shows that it has real people waiting to talk to me 24/7, via three different communication channels.

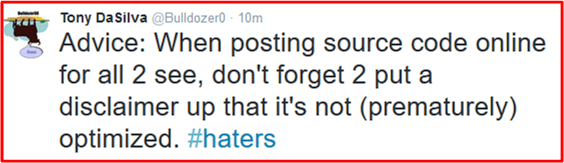

Don’t Forget The Disclaimer

Because of the nature of the subject matter, I’d estimate that it takes me three times as long to write a C++ post as compared to any other topic. Part of that writing/thinking time is burned up trying to anticipate and address questions/critiques from future readers. Thus, from now on, I’m gonna try to follow this advice more closely:

It’s tough to publicly expose your work. In fact, I think that the fear of receiving harsh criticism may be the number one reason why some creative but shy people don’t post any substantive personal content on the web at all. The web can be a mighty unfriendly world for introverts.

If you’re one of these people, but you’re itching to share with the world what you think you know or have learned, give it a try anyway. You might end up receding back into the shadows, but maybe you’ll be able to handle and overcome the adverse feelings that come with the territory. You won’t know unless you give it a go. So go ahead and scratch that itch – at least once.

Stack, Heap, Pool

Update 10/7/15: Because this post lacked a context-setting introduction, I wrote a prequel for it after the fact. Please read the prequel before reading this post.

Three Ways

The figure below shows three ways of allocating memory from within a C++ application: stack, heap, custom written pool.

Comparing Performance

The code below measures the performance of the three allocation methods. It computes and prints the time to allocate 1000, 1MB objects from: the stack, the C++ free store, and a custom-written memory pool (the implementation of Pool appears at the end of this post).

#include <chrono>

#include <iostream>

#include <array>

#include "Pool.h"

class BigObject {

public:

//Each BigObject occupies 1MB of RAM

static const int32_t NUM_BYTES{1000 *1024};

void reset() {} //Required by the Pool class template

void setFirstChar(char c) {byteArray[0] = c;}

private:

std::array<char, NUM_BYTES> byteArray{};

};

//Compare the performance of three types of memory allocation:

//Stack, free store (heap), custom-written pool

int main() {

using namespace std::chrono; //Reduce verbosity of subsequent code

constexpr int32_t NUM_ALLOCS{1000};

void processObj(BigObject* obj);

//Time heap allocations

auto ts = system_clock::now();

for(int32_t i=0; i<NUM_ALLOCS; ++i) {

BigObject* obj{new BigObject{}};

//Do stuff.......

processObj(obj);

}

auto te = system_clock::now();

std::cout << "Heap Allocations took "

<< duration_cast<milliseconds>(te-ts).count()

<< " milliseconds"

<< std::endl;

//Time stack allocations

ts = system_clock::now();

for(int32_t i=0; i<NUM_ALLOCS; ++i) {

BigObject obj{};

//Do stuff.......

processObj(&obj);

} //obj is auto-destroyed here

te = system_clock::now();

std::cout << "Stack Allocations took "

<< duration_cast<milliseconds>(te-ts).count()

<< " milliseconds"

<< std::endl;

//Pool construction time

ts = system_clock::now();

Pool<BigObject, NUM_ALLOCS> objPool;

te = system_clock::now();

std::cout << "Pool construction took "

<< duration_cast<milliseconds>(te-ts).count()

<< " milliseconds"

<< std::endl;

//Time pool allocations

ts = system_clock::now();

for(int32_t i=0; i<NUM_ALLOCS; ++i) {

BigObject* poolObj{objPool.acquire()};

//Do Stuff.......

processObj(poolObj);

}

te = system_clock::now();

std::cout << "Pool Allocations took "

<< duration_cast<milliseconds>(te-ts).count()

<< " milliseconds";

}

void processObj(BigObject* obj) {

obj->setFirstChar('a');

}

The results for a typical program run (gcc 4.9.2, cygwin/Win10, compiler) are shown as follows:

As expected, stack allocation is much faster than heap allocation (3X in this case) because there is no such thing as a “fragmented” stack. The interesting result is how much faster custom pool allocation is than either of the two “standard” out of the box methods. Since each object is 1MB in size, and all of the memory managed by the pool is allocated only once (during construction of the pool object), dynamically acquiring and releasing pointers to the pre-constructed pool objects during runtime is blazingly fast compared to creating a lumbering 1MB object every time the user code needs one.

After you peruse the Pool implementation that follows, I’d love to hear your comments on this post. I’d also appreciate it if you could try to replicate the results I got.

The Pool Class Template – std::array Implementation

Here is my implementation of the Pool class used in the above test code. Note that the Pool class does not use any dynamically resizable STL containers in its implementation. It uses the smarter C++ implementation of the plain ole statically allocated C array. Some safety-critical domains require that no dynamic memory allocation is performed post-initialization – all memory must be allocated either at compile time or upon program initialization.

//Pool.h

#ifndef POOL_H_

#define POOL_H_

#include <array>

#include <algorithm>

#include <memory>

// The OBJ template argument supplied by the user

// must have a publicly defined default ctor and a publicly defined

// OBJ::reset() member function that cleans the object innards so that it

// can be reused again (if needed).

template<typename OBJ, int32_t NUM_OBJS>

class Pool {

public:

//RAII: Fill up the _available array with newly allocated objects.

//Since all objects are available for the user to "acquire"

//on initialization, fill up the _inUse array will nullptrs.

Pool(){

//Fill the _available array with default-constructed objects

std::for_each(std::begin(_available), std::end(_available),

[](OBJ*& mem){mem = new OBJ{};});

//Since no objects are currently in use, fill the _inUse array

//with nullptrs

std::for_each(std::begin(_inUse), std::end(_inUse),

[](OBJ*& mem){mem = nullptr;});

}

//Allows a user to acquire an object to manipulate as she wishes

OBJ* acquire() {

//Try to find an available object

auto iter = std::find_if(std::begin(_available), std::end(_available),

[](OBJ* mem){return (mem not_eq nullptr);});

//Is the pool exhausted?

if(iter == std::end(_available)) {

return nullptr; //Replace this with a "throw" if you need to.

}

else {

//Whoo hoo! An object is available for usage by the user

OBJ* mem{*iter};

//Mark it as in-use in the _available array

*iter = nullptr;

//Find a spot for it in the _inUse list

iter = std::find(std::begin(_inUse), std::end(_inUse), nullptr);

//Insert it into the _inUse list. We don't

//have to check for iter == std::end(_inUse)

//because we are fully in control!

*iter = mem;

//Finally, return the object to the user

return mem;

}

}

//Returns an object to the pool

void release(OBJ* obj) {

//Ensure that the object is indeed in-use. If

//the user gives us an address that we don't own,

//we'll have a leak and bad things can happen when we

//delete the memory during Pool destruction.

auto iter = std::find(std::begin(_inUse), std::end(_inUse), obj);

//Simply return control back to the user

//if we didn't find the object in our

//in-use list

if(iter == std::end(_inUse)) {

return;

}

else {

//Clear out the innards of the object being returned

//so that the next user doesn't have to "remember" to do it.

obj->reset();

//temporarily hold onto the object while we mark it

//as available in the _inUse array

OBJ* mem{*iter};

//Mark it!

*iter = nullptr;

//Find a spot for it in the _available list

iter = std::find(std::begin(_available), std::end(_available), nullptr);

//Insert the object's address into the _available array

*iter = mem;

}

}

~Pool() {

//Cleanup after ourself: RAII

std::for_each(std::begin(_available), std::end(_available),

std::default_delete<OBJ>());

std::for_each(std::begin(_inUse), std::end(_inUse),

std::default_delete<OBJ>());

}

private:

//Keeps track of all objects available to users

std::array<OBJ*, NUM_OBJS> _available;

//Keeps track of all objects in-use by users

std::array<OBJ*, NUM_OBJS> _inUse;

};

#endif /* POOL_H_ */

The Pool Class Template – std::multiset Implementation

For grins, I also implemented the Pool class below using std::multiset to keep track of the available and in-use objects. For large numbers of objects, the acquire()/release() calls will most likely be faster than their peers in the std::array implementation, but the implementation violates the “no post-intialization dynamically allocated memory allowed” requirement – if you have one.

Since the implementation does perform dynamic memory allocation during runtime, it would probably make more sense to pass the size of the pool via the constructor rather than as a template argument. If so, then functionality can be added to allow users to resize the pool during runtime if needed.

//Pool.h

#ifndef POOL_H_

#define POOL_H_

#include <algorithm>

#include <set>

#include <memory>

// The OBJ template argument supplied by the user

// must have a publicly defined default ctor and a publicly defined

// OBJ::reset() member function that cleans the object innards so that it

// can be reused again (if needed).

template<typename OBJ, int32_t NUM_OBJS>

class Pool {

public:

//RAII: Fill up the _available set with newly allocated objects.

//Since all objects are available for the user to "acquire"

//on initialization, fill up the _inUse set will nullptrs.

Pool(){

for(int32_t i=0; i<NUM_OBJS; ++i) {

_available.insert(new OBJ{});

_inUse.insert(nullptr);

}

}

//Allows a user to acquire an object to manipulate as she wishes

OBJ* acquire() {

//Try to find an available object

auto iter = std::find_if(std::begin(_available), std::end(_available),

[](OBJ* mem){return (mem not_eq nullptr);});

//Is the pool exhausted?

if(iter == std::end(_available)) {

return nullptr; //Replace this with a "throw" if you need to.

}

else {

//Whoo hoo! An object is available for usage by the user

OBJ* mem{*iter};

//Mark it as in-use in the _available set

_available.erase(iter);

_available.insert(nullptr);

//Find a spot for it in the _inUse set

iter = std::find(std::begin(_inUse), std::end(_inUse), nullptr);

//Insert it into the _inUse set. We don't

//have to check for iter == std::end(_inUse)

//because we are fully in control!

_inUse.erase(iter);

_inUse.insert(mem);

//Finally, return the object to the user

return mem;

}

}

//Returns an object to the pool

void release(OBJ* obj) {

//Ensure that the object is indeed in-use. If

//the user gives us an address that we don't own,

//we'll have a leak and bad things can happen when we

//delete the memory during Pool destruction.

auto iter = std::find(std::begin(_inUse), std::end(_inUse), obj);

//Simply return control back to the user

//if we didn't find the object in our

//in-use set

if(iter == std::end(_inUse)) {

return;

}

else {

//Clear out the innards of the object being returned

//so that the next user doesn't have to "remember" to do it.

obj->reset();

//temporarily hold onto the object while we mark it

//as available in the _inUse array

OBJ* mem{*iter};

//Mark it!

_inUse.erase(iter);

_inUse.insert(nullptr);

//Find a spot for it in the _available list

iter = std::find(std::begin(_available), std::end(_available), nullptr);

//Insert the object's address into the _available array

_available.erase(iter);

_available.insert(mem);

}

}

~Pool() {

//Cleanup after ourself: RAII

std::for_each(std::begin(_available), std::end(_available),

std::default_delete<OBJ>());

std::for_each(std::begin(_inUse), std::end(_inUse),

std::default_delete<OBJ>());

}

private:

//Keeps track of all objects available to users

std::multiset<OBJ*> _available;

//Keeps track of all objects in-use by users

std::multiset<OBJ*> _inUse;

};

#endif /* POOL_H_ */

Unit Testing

In case you were wondering, I used Phil Nash’s lightweight Catch unit testing framework to verify/validate the behavior of both Pool class implementations:

TEST_CASE( "Allocations/Deallocations", "[Pool]" ) {

constexpr int32_t NUM_ALLOCS{2};

Pool<BigObject, NUM_ALLOCS> objPool;

BigObject* obj1{objPool.acquire()};

REQUIRE(obj1 not_eq nullptr);

BigObject* obj2 = objPool.acquire();

REQUIRE(obj2 not_eq nullptr);

objPool.release(obj1);

BigObject* obj3 = objPool.acquire();

REQUIRE(obj3 == obj1);

BigObject* obj4 = objPool.acquire();

REQUIRE(obj4 == nullptr);

objPool.release(obj2);

BigObject* obj5 = objPool.acquire();

REQUIRE(obj5 == obj2);

}

==============================================

All tests passed (5 assertions in 1 test case)

C++11 Features

For fun, I listed the C++11 features I used in the source code:

- * auto

- * std::array<T, int>

- * std::begin(), std::end()

- * nullptr

- * lambda functions

- * Brace initialization { }

- * std::chrono::system_clock, std::chrono::duration_cast<T>

- * std::default_delete<T>

Did I miss any features/classes? How would the C++03 implementations stack up against these C++11 implementations in terms of readability/understandability?

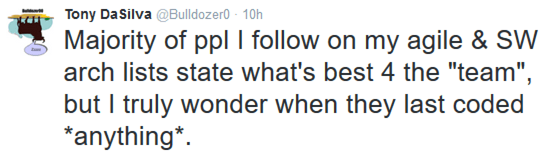

Loneliness Mitigation

As a programmer who devilishly loves to poke the “agilencia” in the eye on Twitter, I sometimes feel like a lone wolf searching for a pack to join.

In order to cure my loneliness, I decided to lure some fellow programmers out of the shadows to see where they stand. Thus, I seeded my timeline with this provocative tweet.

Looky here! I somewhat succeeded in achieving my goal of “loneliness mitigation”:

Don’t get me wrong, I really like and admire some members of the non-programming agilencia. I’m actually sorry that I used the the word “majority” in my seed tweet.

Dude, Let’s Swarm!

Whoo hoo! I just got back from a 3 day, $2,000 training course in “swarm programming.” After struggling to make it though the unforgiving syllabus, I earned my wings along with the unalienable right to practice in this new and exciting way of creating software. Hyper-productive Scrum teams are so yesterday. Turbo-charged swarm teams are the wave of the future!

I found it strangely interesting that not one of my 30 (30 X $2K = 60K) classmates failed the course. But hey, we’re now ready and willing to swarm our way to success. There’s no stoppin’ us.

Robust And Resilient

A few posts ago, I laid down a timeline of significant events in the history of the Bitcoin movement. All of those events are positive developments that give the reader an impression of steady forward progress. However, it has been no bed of roses for the world’s first decentralized currency system. To highlight this fact, I decided to superimpose four of the events (in blue) that could have signaled the death of Bitcoin – but didn’t.

The Silk Road disaster, the China crackdown, the Mt. Gox implosion, or the dire SEC warning each in their own right could have caused the value of Bitcoin to go back to its initial value of zero and stay there – but it didn’t. Thus far, Bitcoin has shown remarkable robustness and resiliency. Perhaps it’s even antifragile – gaining strength with each attempt to kill it.

As long as enough people believe that Bitcoin has value, then it will have value. As cell phones become more and more affordable to the poor and third world countries continue to act fiscally irresponsible with their fiat currencies, Bitcoin’s volatility will decrease and its utility as a fast, low fee, direct, mechanism of economic exchange will increase.

Bitcoin was never designed out of the box to “fit in” with the established ways of dealing with money through centralized institutions that can collapse or go bankrupt via greed/corruption. Perhaps it never will fit in, but Bitcoin can exist side-by-side with the established big wigs; acting as a deterrent to incompetent governments (Zimbabwe, Greece, Cyprus?) and serving as an escape valve to those affected by that incompetence.