Archive

Rules, Exceptions, Guidelines

Unlike natural laws (on the macroscopic level) which unremorsefully allow no exceptions, I think all human concocted rules should be flexible to exceptions, no? If you believe that, then maybe the word “rule” should be replaced with “guideline”. Doing this can be interpreted as splitting hairs, but I think it may positively affect those who are required to operate by the “rules”. It shows respect and implies that some freedom is allowed to continuously improve things. Since the yearning for freedom is built into the fiber of every human being, those in positions of authority who conjure up the “rules” should take heed.

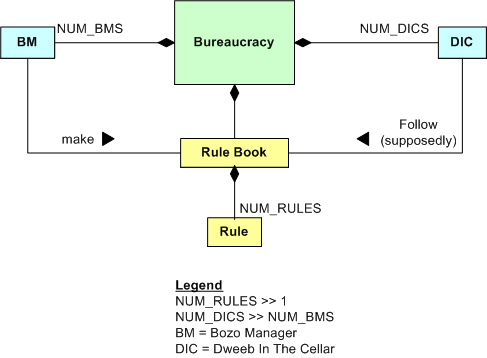

Note: The model above is a UML “class diagram”, which is used to depict the static structure of a system. Other UML diagrams can be used to model the behaviors of a system. The diagram can be interpreted as follows:

- A bureaucracy has NUM_BMS BMs and NUM_DICS DICs and a Rule Book.

- The BMs make the rule book, which has NUM_RULES (usually a boatload) rules.

- The DICs are obliged to follow the rules, written or unwritten (but understood) – or else.

Hold The Details, Please

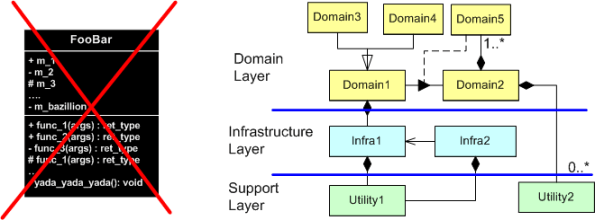

When documenting software designs (in UML, of course) before, during, or after writing code, I don’t like to put too much detail in my models. By details, I mean exposing all public/protected/private data members and functions and all intra-member processing sequences within each class. I don’t like doing it for these reasons:

- I don’t want to get stuck in a time-busting, endless analysis paralysis loop.

- I don’t want a reviewer or reader to lose the essence of the design in a sea of unnecessary details that obscure the meaning and usefulness of the model.

- I don’t want every little code change to require a model change – manual or automated.

I direct my attention to the higher levels of abstraction, focusing on the layered structure of the whole. By “layered structure”, I mean the creation and identification of all the domain level classes and the next lower level, cross-cutting infrastructure and utility classes. More importantly, I zero in on all the relationships between the domain and infrastructure classes because the real power of a system, any system, emerges from the dynamic interactions between its constituent parts. Agonizing over the details within each class and neglecting the inter-class relationships for a non-trivial software system can lead to huge, incoherent, woeful classes and an unmaintainable downstream mess. D’oh!

How about you? What personal guidelines do you try to stick to when modeling your software designs? What, you don’t “do documentation“? If you’re looking to move up the value chain and become more worthy to your employer and (more importantly) to yourself, I recommend that you continuously learn how to become a better, “light” documenter of your creations. But hey, don’t believe a word I say because I don’t have any authority-approved credentials/titles and I like to make things up.

Powerful Tools

Cybernetician W. Ross Ashby‘s law of requisite variety states that “only variety can effectively control variety“. Another way of stating the law is that in order to control an innately complex problem with N degrees of freedom, a matched solution with at least N degrees of freedom is required. However, since solutions to hairy socio-technical problems introduce their own new problems into the environment, over-designing a problem controller with too many extra degrees of freedom may be worse than under-designing the controller.

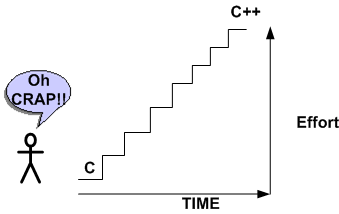

In an analogy with Ashby’s law, it takes powerful tools to solve powerful problems. Using a hammer where only a sledgehammer will get the job done produces wasted effort and leaves the problem unsolved. However, learning how to use and wield powerful new tools takes quite a bit of time and effort for non-genius people like me. And most people aren’t willing to invest prolonged time and effort to learn new things. Relative to adolescents, adults have an especially hard time learning powerful new tools because it requires sustained immersion and repetitive practice to become competent in their usage. That’s why they typically don’t stick with learning a new language or learning how to play an instrument.

In my case, it took quite a bit of effort and time before I successfully jumped the hurdle between the C and C++ programming languages. Ditto for the transition from ad-hoc modeling to UML modeling. These new additions to my toolbox have allowed me to tackle larger and more challenging software problems. How about you? Have you increased your ability to solve increasingly complex problems by learning how to wield commensurately new and necessarily complex tools and techniques? Are you still pointing a squirt gun in situations that cry out for a magnum?

Requirements Before, Design After

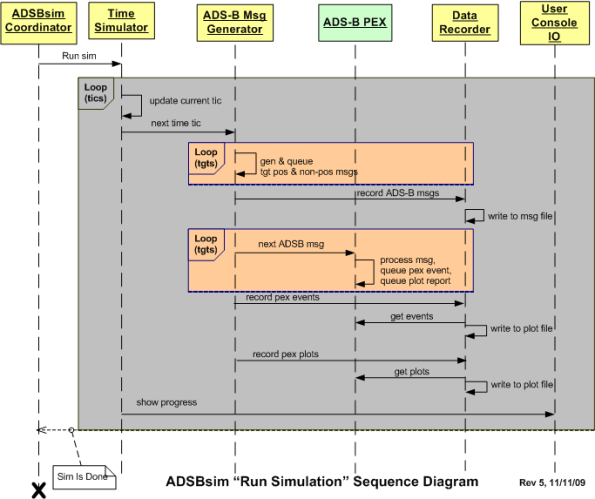

The figure below depicts a UML sequence diagram of the behavior of a simulator during the execution of a user defined scenario. Before the code has been written and tested, one can interpret this diagram as a set of interrelated behavioral requirements imposed on the software. After the code has been written, it can be considered a design artifact that reflects what the code does at a higher level of abstraction than the code itself.

Interpretations like this give credence to Alan Davis’s brilliant quote:

One man’s requirement is another man’s design

Here’s a question. Do you think that specifying the behavior requirements in the diagram would have been best conveyed via a user story or a use case description?

Here’s a question. Do you think that specifying the behavior requirements in the diagram would have been best conveyed via a user story or a use case description?

Shallmeisters, Get Over It.

If you pick up any reference article or book on requirements engineering, I think you’ll find that most “experts” in the field don’t obsess over “shalls”. They know that there’s much more to communicating requirements than writing down tidy, useless, fragmented, one line “shall” statements. If you don’t believe me, then come out of your warm little cocoon and explore for yourself. Here are just a few references:

http://www.amazon.com/Process-System-Architecture-Requirements-Engineering/dp/0932633412/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1257672507&sr=1-3

With the growing complexity of software-intensive systems that need to be developed for an org to remain sustainable and relevant, the so-called venerable “shall” is becoming more and more dinosaurish. Obviously, there will always be a place for “shalls” in the development process, but only at the most superficial and highest level of “requirements specification”; which is virtually useless to the hardware, software, network, and test engineers who have to build the system (while you watch from the sidelines and “wait” until the wrong monstrosity gets built so you can look good criticizing it for being wrong).

So, what are some alternatives to pulling useless one dimensional “shalls” out of your arse? How about mixing and matching some communication tools from this diversified, two dimensional menu:

- UML Class diagrams

- UML Use Case diagrams

- UML Deployment diagrams

- UML Activity diagrams

- UML State Machine diagrams

- UML Sequence diagrams

- Use Case Descriptions

- User Stories

- IDEF0 diagrams

- Data Flow Diagrams

- Control Flow Diagrams

- Entity-Relationship diagrams

- SysML Block Definition diagrams

- SysML Internal Block Definition diagrams

- SysML Requirements diagrams

- SysML Parametric diagrams

Get over it, add a second dimension to your view, move into this century, and learn something new. If not for your company, then for yourself. As the saying goes, “what worked well in the past might not work well in the future”.

I’m Finished

I just finished (100% of course <-LOL!) my latest software development project. The purpose of this post is to describe what I had to do, what outputs I produced during the effort, and to obtain your feedback – good or bad.

The figure below shows a simple high level design view of an existing real-time, software-intensive, revenue generating product that is comprised of hundreds of thousands of lines of source code. Due to evolving customer requirements, a major redesign and enhancement of the application layer functionality that resides in the Channel 3 Target Extractor is required.

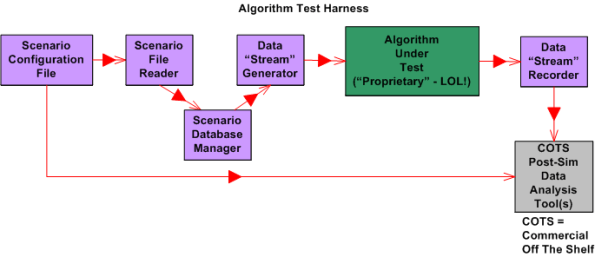

The figure below shows the high level static structure of the “Enhanced Channel 3 Target Extractor” test harness that was designed and developed to test and verify that the enhanced channel 3 target extractor works correctly. Note that the number of high level conceptual test infrastructure classes is 4 compared to the lone, single product class whose functionality will be migrated into the product code base.

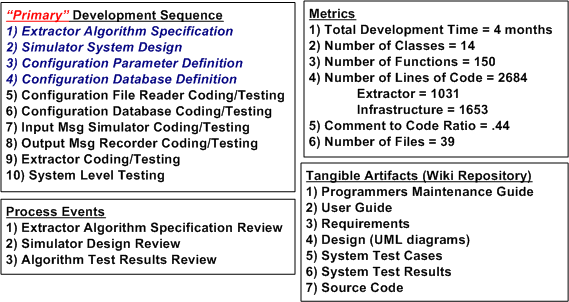

The figure below shows a post-project summary in terms of: the development process I used, the process reviews I held, the metrics I collected, and the output artifacts that I produced. Summarizing my project performance via the often used, simple-minded metric that old school managers love to use; lines of code per day, yields the paltry number of 22.

Since my average “velocity” was a measly 22 lines of code per day, do you think I underperformed on this project? What should that number be? Do you summarize your software development projects similar to this? Do you just produce source code and unit tests as your tangible output? Do you have any idea what your performance was on the last project you completed? What do you think I did wrong? Should I have just produced source code as my output and none of the other 6 “document” outputs? Should I have skipped steps 1 through 4 in my development process because they are non-agile “documentation” steps? Do you think I followed a pure waterfall process? What say you?

Standard CCH Blueprint

The figure below is a “bent” UML (Unified Modeling Language) class diagram of a standard corpo CCH (Command and Control Hierarchy). Association connectors were left off because the diagram would be a mess and the only really important relationships are the adjacent step-by-step vertical connections. Each box represents a “classifier”, which is a blueprint for stamping out objects that behave according to the classifier blueprint. The top compartment contains the classifier name, the second compartment contains its attributes, and the third compartment houses the classifier’s behaviors. Except for the DIC Product Development Team, the attributes of all other classifiers were elided away because the intent was to focus on the standard cookie-cutter behaviors of each object in the “system”. Of course, the org you work for is not an instantiation of this system, right?

Useless Cases

Despite the blasphemous title of this blarticle, I think that “use cases” are a terrific tool for capturing a system’s functional requirements out of the ether; for the right class of applications. Nevertheless, I agree with requirements “expert” Karl Wiegers, who states the following in “More About Software Requirements: Thorny Issues And Practical Advice“:

However, use cases are less valuable for projects involving data warehouses, batch processes, hardware products with embedded control software, and computationally intensive applications. In these sorts of systems, the deep complexity doesn’t lie in the user-system interactions. It might be worthwhile to identify use cases for such a product, but use case analysis will fall short as a technique for defining all the system’s behavior.

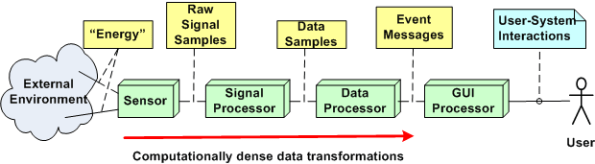

I help to define, specify, design, code, and test embedded (but relatively “big”) software-intensive sensor systems for the people-transportation industry. The figure below shows a generic, pseudo-UML diagram of one of these systems. Every component in the string is software-intensive. In this class of systems, like Karl says, “the deep complexity doesn’t lie in the user-system interactions”. As you can see, there’s a lot of special and magical “stuff” going on behind the GUI that the user doesn’t know about, and doesn’t care to know about. He/she just cares that the objects he/she wants to monitor show up on the screen and that the surveillance picture dutifully provided by the system is an accurate representation of what’s going on in the real world outside.

A list of typical functions for a product in this class may look like this:

- Display targets

- Configure system

- Monitor system operation

- Tag target

- Control system operation

- Perform RF signal filtering

- Perform signal demodulation

- Perform signal detection

- Perform false signal (e.g. noise) rejection

- Perform bit detection, extraction, and message generation

- Perform signal attribute (e.g. position, velocity) estimation

- Perform attribute tracking

Notice that only the top five functions involve direct user interaction with the product. Thus, I think that employing use cases to capture the functions required to provide those capabilities is a good idea. All the dirty and nasty”perform” stuff requires vertical, deep mathematical expertise and specification by sensor domain experts (some of whom, being “expert specialists”, think they are Gods). Thus, I think that the classical “old and unglamorous” Software Requirements Specification (SRS) method of defining the inputs/processing/output sequences (via UML activity diagrams and state machine diagrams) blows written use case descriptions out of the water in terms of Return On Investment (ROI) and value transferred to software developers.

Clueless Bozo Managers (BMs) and senior wannabe-a-BM developers who jump on the “use cases for everything” bandwagon (but may have never written a single use case description themselves) waste company time and money trying to bully “others” into ramming a square peg into a round hole. But they look hip, on the ball, and up to date doing it. And of course, they call it leadership.

My “Status” As Of 09-27-09

I recently finished a 2 month effort discovering, developing, and recording a state machine algorithm that produces a stream of integrated output “target” reports from a continuous stream of discrete, raw input message fragments. It’s not rocket science, but because of the complexity of the algorithm (the devil’s always in the details), a decision was made to emulate this proprietary algorithm in multiple, simulated external environmental scenarios. The purpose of the emulation-plus-simulation project is to work out the (inevitable) kinks in the algorithm design prior to integrating the logic into an existing product and foisting it on unsuspecting customers :^) .

The “bent” SysML diagram below shows the major “blocks” in the simulator design. Since there are no custom hardware components in the system, except for the scenario configuration file, every SysML block represents a software “class”.

Upon launch, the simulator:

- Reads in a simple, flat, ASCII scenario configuration file that specifies the attributes of targets operating in the simulated external environment. Each attribute is defined in terms of a <name=value> token pair.

- Generates a simulated stream of multiplexed input messages emitted by the target constellation.

- Demultiplexes and processes the input stream in accordance with the state machine algorithm specification to formulate output target reports.

- Records the algorithm output target report stream for post-simulation analysis via Commercial Off The Shelf (COTS) tools like Excel and MATLAB.

I’m currently in the process of writing the C++ code for all of the components except the COTS tools, of course. On Friday, I finished writing, unit testing, and integration testing the “Simulation Initialization” functionality (use case?) of the simulator.Yahoo!

The diagram below zooms in on the front end of the simulator that I’ve finished (100% of course) developing; the “Scenario File Reader” class, and the portion of the in-memory “Scenario Database Manager” class that stores the scenario configuration data in the two sub-databases.

The next step in my evil plan (moo ha ha!) is to code up, test, and integrate the much-more-interesting “Data Stream Generator” class into the simulator without breaking any of the crappy code that has already been written. 🙂

If someone (anyone?) actually reads this boring blog and is interested in following my progress until the project gets finished or canceled, then give me a shoutout. I might post another status update when I get the “Data Stream Generator” class coded, tested, and integrated.

What’s your current status?

Architectural, Mechanistic, And Detailed

Bruce Powel Douglass is one of my favorite embedded systems development mentors. One of his ideas is to categorize the activity of design into three levels of increasingly detailed abstraction:

- Architectural (5 views)

- Mechanistic

- Detailed

The SysML figure below tries to depict the conceptual differences between these levels. (Even if you don’t know the SysML, can you at least viscerally understand the essence of what the drawings are attempting to communicate?)

Since the size, algorithmic density, and safety critical nature of the software intensive systems that I’ve helped to develop require what the agile community mocks as BDUF (Big Design Up Front), I’ve always communicated my “BDUF” designs in terms of the first and third abstractions. Thus, the mechanistic design category is sort of new to me. I like this category because it shortens the gulf of understanding between the architectural and the detailed design levels of abstraction. According to Mr. Douglass, “mechanistic design” is the act of optimizing a system at the level of an individual collaboration ( a set of UML classes or SysML blocks working closely together to realize a single use case). From now on, I’m gonna follow his three tier taxonomy in communicating future designs, but only when it’s warranted, of course (I’m not a religious zealot for or against any method), .

BTW, if you don’t do BDUF, you might get CUDO (Crappy and Unmaintanable Design Out back). Notice that I said “might” and not “will”.