Archive

It’s All About That Jell

Agile, Traditional, Lean, Burndown Charts, Kanban Boards, Earned Value Management Metrics, Code Coverage, Static Code Analysis, Coaches, Consultants, Daily Standup Meetings, Weekly Sit Down Meetings, Periodic Program/Project Reviews. All the shit managers obsess over doesn’t matter. It’s all about that Jell, ’bout that jell, ’bout that jell.

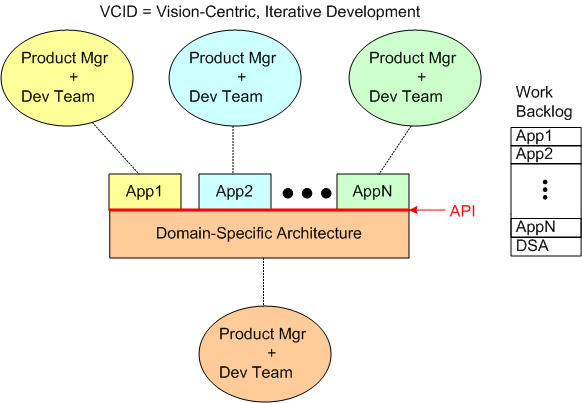

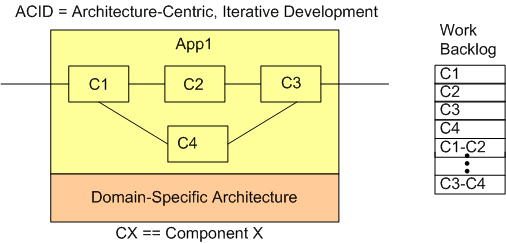

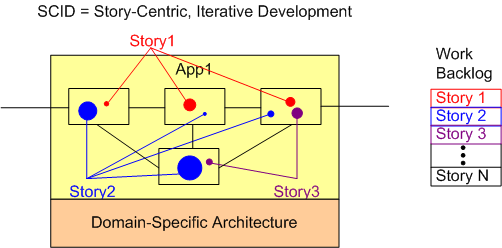

VCID, ACID, SCID

First, we have VCID:

In VCID mode, we iteratively define, at a coarse level of granularity, what the Domain-Specific Architecture (DSA) is and what the revenue-generating portfolio of Apps that we’ll be developing are.

Next up, we have ACID:

In ACID mode, we’ll iteratively define, at at finer level of detail, what each of our Apps will do for our customers and the components that will comprise each App.

Then, we have SCID, where we iteratively cut real App & DSA code and implement per-App stories/use cases/functions:

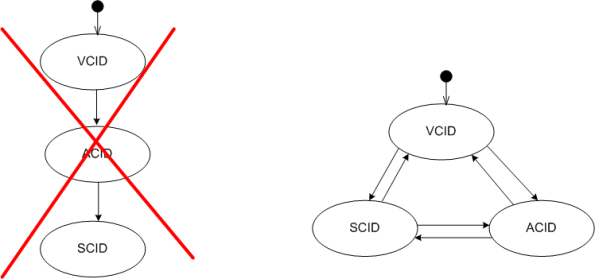

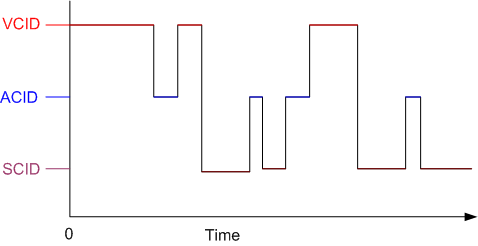

But STOP! Unlike the previous paragraphs imply, the “CID”s shouldn’t be managed as a sequential, three step, waterfall execution from the abstract world of concepts to the real world of concrete code. If so, your work is perhaps doomed. The CIDs should inform each other. When work in one CID exposes an error(s) in another CID, a transition into the flawed CID state should be executed to repair the error(s).

Managed correctly, your product development system becomes a dynamically executing, inter-coupled, set of operating states with error-correcting feedback loops that steer the system toward its goal of providing value to your customers and profits to your coffers.

Nothing Is Unassailable

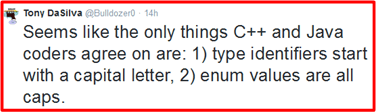

I recently posted a tidbit on Twitter which I thought was benignly unassailable:

Of course, Twitter being Twitter, I was wrong – and that’s one of the reasons why I love (and hate) Twitter. When your head gets too inflated, Twitter can deflate it as fast as a pin pops a balloon.

Yes, But You Will Know

In recounting his obsession with quality, I recall an interview where Steve Jobs was telling a reporter about painting a fence with his father when he was a young boy. There was a small section in a corner of the yard, behind a shed and fronted by bushes, that was difficult to lay a brush on. Steve asked his dad: “Do I really have to paint that section? Nobody will know that it’s not painted.” His father simply said: “Yes, but you will know.”

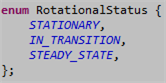

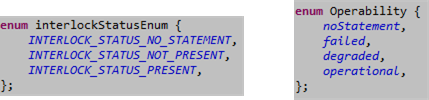

It is pretty much a de-facto standard in the C++ (and Java) world that enum type names start with a capital letter and that enumeration values are all capitalized, with underscores placed between multi-word names:

Now, assume you stumble across some sloppy work like this in code that must be formally shared between two different companies:

Irked by the obvious sloppiness, and remembering the Steve Jobs story, you submit the following change request to the formal configuration control board in charge of ensuring consistency, integrity, and quality of all the inter-company interfaces:

What would you do if your request was met with utter silence – no acknowledgement whatsoever? Pursue it further, or call it quits? Is silence on a small issue like this an indicator of a stinky cultural smell in the air, or is the ROI to effect the change simply not worth it? If the ROI to make the change is indeed negative, could that be an indicator of something awry with the change management process itself?

How hard, and how often, do you poke the beast until you choose to call it quits and move on? Seriously, you surely do poke the beast at least once in a while… err, don’t you?

Additive Vs Multiplicative

You may not believe this, but overall, I like “agile” management and coding practices- where they fit. The most glaring shortcoming that I, and perhaps only I, perceive in the “agile” body of knowledge concerns the dearth of guidance for handling both the social and technical dependencies present in every software development endeavor. The larger the project (or whatever you #noprojects community members want to call it), the more tangled the inter-dependencies. There are, simultaneously: social couplings, technical couplings, and the nastiest type of coupling of all: socio-technical couplings.

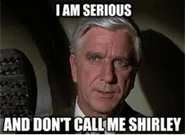

The best analogy I can think of to express my thoughts on the agile dependencies black hole is the linear vs multiplicative complexity conundrum as expressed so elegantly by Bertrand Meyer in his book, “Agile!“. But instead of the family friendly linguini and lasagna images Mr. Meyer employs in his book, I, of course, choose to use imagery more in line with the blasphemous theme of this blog:

The complexity of the system is at least equal to the product of the problem and solution complexities. At worst, there are exponents associated with one or both multiplicands.

One Word

I’ve been waiting patiently (freakin’ impatiently?) for 10+ years for some word, any word, to dethrone “agile” as the most frequently seen word on book, video, and article titles in the software industry. Thanks to the highly esteemed Gartner consulting firm, perhaps we have a viable candidate:

“Bimodal IT refers to having two modes of IT, each designed to develop and deliver information- and technology-intensive services in its own way. Mode 1 is traditional, emphasizing scalability, efficiency, safety and accuracy. Mode 2 is non-sequential, emphasizing agility and speed.” – Gartner IT Glossary

Personally, I like the word “Tradagile” better than “Bimodal“. It’s lighter, less stuffy.

I’m goin’ Bimodal! W00t!

More Effective Than, But Not As Scalable As

If you feel you have something to offer the world, the best way to expose and share your ideas/experiences/opinions/knowledge/wisdom is to release it from lock down in your mind and do the work necessary to get it into physical form. Write it down, or draw it up, or record it. Then propagate it out into the wild blue yonder through the greatest global communication system yet known to mankind: the internet.

You are not personally scalable, but because of the power of the internet, the artifacts you create are. Fuggedabout whether anybody will pay attention to what you create, manifest, and share. Birth it and give it the possibility to grow and prosper. Perhaps no one’s eyeballs or ears other than yours will ever come face to face with your creations, but your children will be patiently waiting for any and all adopters that happen to come along.

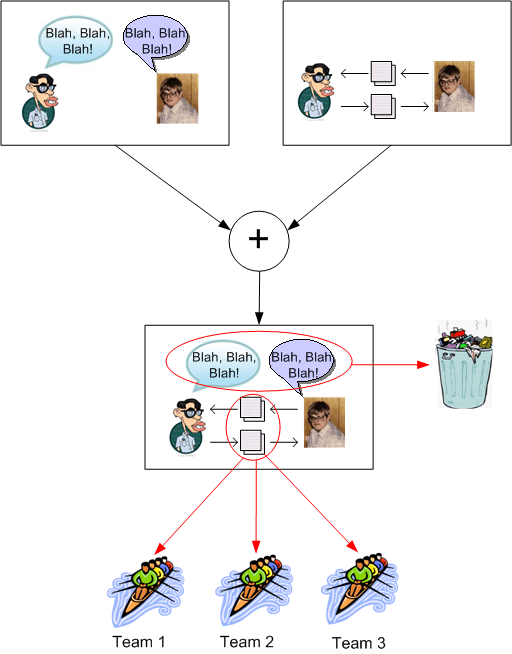

The agilista community is fond of trashing the “traditional” artifact-exchange method of communication and extolling the virtues of the effectiveness of close proximity, face-to-face, verbal exchange. Alistair Cockburn even has some study-backed curves that bolster the claim. BD00 fully agrees with the “effectiveness” argument, but just like the source code is not the whole truth, face-to-face communication is not the whole story. As noted in the previous paragraph, a personal conversation is not scalable.

Face to face, verbal communication may be more effective than artifact exchange, but it’s ephemeral, not archive-able, and not nearly as scalable. And no half-assed scribblings on napkins, envelopes, toilet paper, nor index cards solve those shortcomings on anything but trivial technical problems.

Both Inane And Insane

Let’s start this post off by setting some context. What I’m about to spout concerns the development of large, complex, software systems – not mobile apps or personal web sites. So, let’s rock!

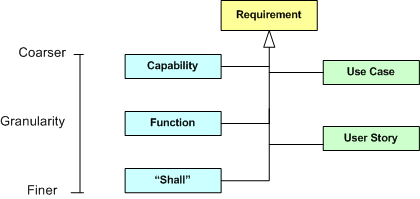

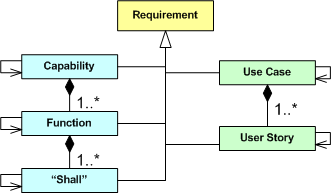

The UML class diagram below depicts a taxonomy of methods for representing and communicating system requirements.

On the left side of the diagram, we have the traditional methods: expressing requirements as system capabilities/functions/”shalls”. On the right side of the diagram, we have the relatively newer artifacts: use cases and user stories.

When recording requirements for a system you’re going to attempt to build, you can choose a combination of methods as you (or your process police) see fit. In the agile world, the preferred method (as evidenced by 100% of the literature) is to exclusively employ fine-grained user stories – classifying all the other, more abstract, overarching, methods as YAGNI or BRUF.

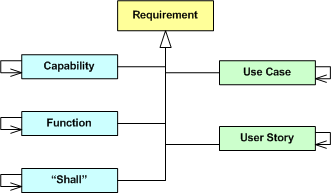

As the following enhanced diagram shows, whichever method you choose to predominantly start recording and communicating requirements to yourself and others, at least some of the artifacts will be inter-coupled. For example, if you choose to start specifying your system as a set of logically cohesive capabilities, then those capabilities will be coupled to some extent – regardless of whether you consciously try to discover and expose those dependencies or not. After all, an operational system is a collection of interacting parts – not a bag of independent parts.

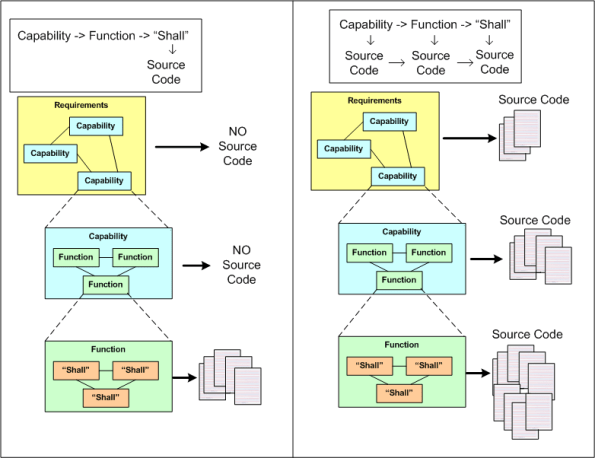

Let’s further enhance our class diagram to progressively connect the levels of granularity as follows:

If you start specifying your system as a set of coarse-grained, interacting capabilities, it may be difficult to translate those capabilities directly into code components, packages, and/or classes. Thus, you may want to close the requirements-to-code intellectual gap by thoughtfully decomposing each capability into a set of logically cohesive, but loosely coupled, functions. If that doesn’t bridge the gap to your liking, then you may choose to decompose each function further into a finer set of logically cohesive, but loosely coupled, “shall” statements. The tradeoff is time upfront for time out back:

- Capabilities -> Source Code

- Use Cases – > Source Code

- Capabilities -> Functions -> Source Code

- Use Case -> User Story -> Source Code

- Capabilities -> Functions -> “Shalls” -> Source Code

Note that, taken literally, the last bullet implies that you don’t start writing ANY code until you’ve completed the full, two step, capabilities-to-“shalls” decomposition. Well, that’s a croc o’ crap. You can, and should, start writing code as soon as you understand a capability and/or function well enough so that you can confidently cut at least some skeletal code. Any process that prohibits writing a single line of code until all the i’s are dotted and all the t’s are crossed and five “approval” signatures are secured is, as everyone (not just the agile community) knows, both inane and insane.

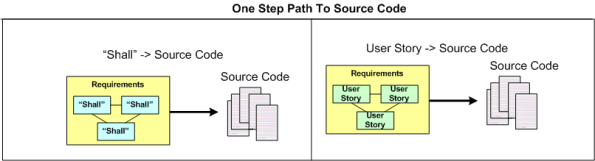

Of course, simple projects don’t need no stinkin’ multi-step progression toward source code. They can bypass the Capability, Function, and Use Case levels of abstraction entirely and employ only fine grained “shalls” or User Stories as the method of specification.

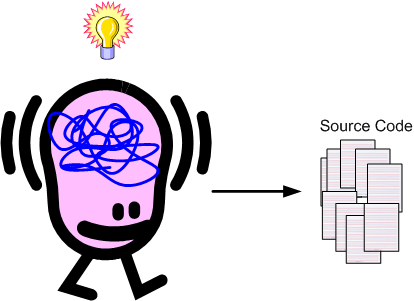

On the simplest of projects, you can even go directly from thoughts in your head to code:

The purpose of this post is to assert that there is no one and only “right” path in moving from requirements to code. The “heaviness” of the path you decide to take should match the size, criticality, and complexity of the system you’ll be building. The more the mismatch, the more the waste of time and effort.