Archive

Basement Garden

After concocting yesterday’s irreverent post, the universe whispered in my ear:

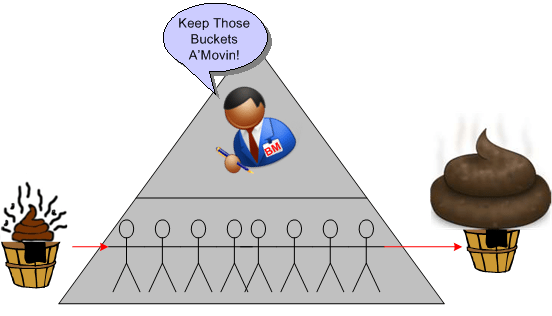

Put a visual to the saying: DYSCOs often treat their “associates” like mushrooms: Down in the basement and well fed with chit.

Since I don’t want to piss the universe off, here t’is:

Toxic Fungus

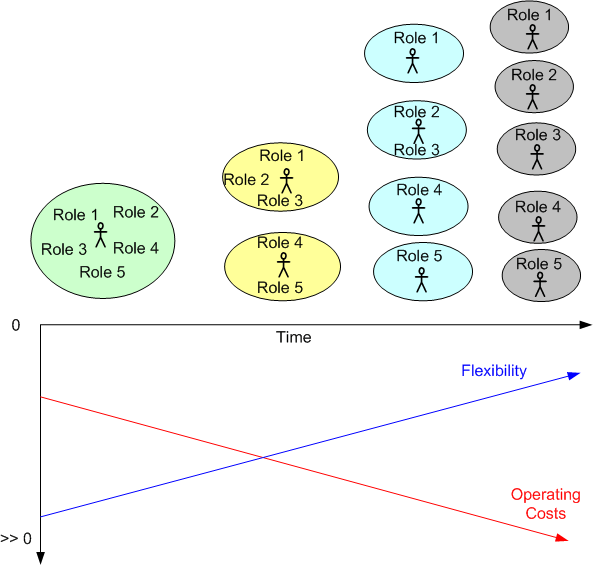

Unless due diligence is performed on the part of an org’s leadership junta/cabal/politburo, fragmentation of responsibility and unessential specialization can easily creep into “the system” – triggering a bloat in costs and increased operational rigidity. Like a toxic fungus, not only is it tough to prevent, it’s tough to eradicate. D’oh! I hate when that happens.

Six “C”s

Whoo Hoo! I found another non-mainstream heretic to learn from: Mr. Alfie Kohn.

I’m currently in the process of reading Mr. Kohn’s book: “Punished By Rewards“. PBR is a well researched and eloquently written diatribe against anything that reeks of the Skinnerian dogma: “Do This And You’ll Get That“. Mr. Kohn is a staunch opponent of rewards, punishments and any other form of external control.

People don’t resist change. They resist being changed. – Unknown

Applying his rhetoric to parenting, the classroom, and the corpricracy, Alfie cites study after study and experiment after experiment in which all external motivational actions perpetrated by “authorities” achieve only short term results while destroying intrinsic motivation and ensuring long term, negative consequences – like reluctant compliance and uncreative, mechanistic doing.

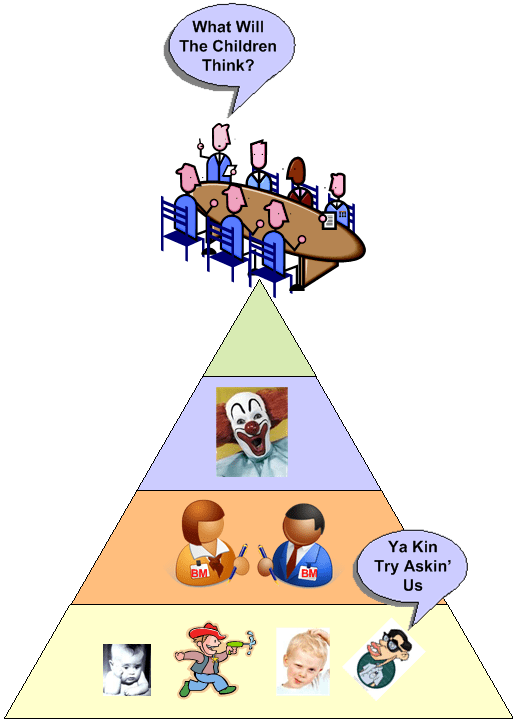

The classic (and reasonable) question posed most often to Mr. Kohn is “if rewards and punishments don’t work, what alternatives are there Mr. Smartie Pants?“. Of course, he doesn’t have a nice and tidy answer, but he cites three “C”s: Choice, Collaboration, and Content, as the means of bringing out the willful best in children, students, and employees.

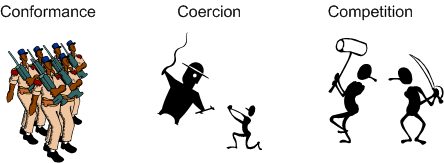

Much like Dan Pink‘s big 3 (mastery, autonomy, and purpose), creating an environment and supporting culture in which Alfie’s three “C”s are manifest is devilishly difficult. In familial, educational, and corporate systems, their hierarchical structures naturally suppress Alfie’s 3 “C”s while nurturing this 3 “C” alternative:

House Of Cards

Executive Proposal

The lowly esteemed and dishonorable BD00 proposes to executives everywhere:

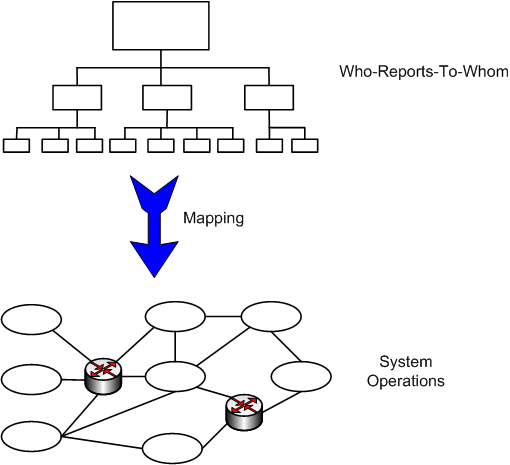

Whenever you change your org, supply the minions with TWO complementary org charts: the usual (yawn) who-reports-to-whom chart and a system operational structure chart.

Creating the first one is an easy task; the second one, not-so. That’s why you’ve never seen one.

The funny thing is, every borg has a “System Operational Structure” chart regardless of whether it’s known or (most likely) not. Reshuffling the “Who-Reports-To-Whom” chart without knowing and consulting with the “Systems Operational Structure” chart doesn’t improve operations (unless the reshuffler gets lucky), it justs changes who to blame when sub par performance persists after the latest and greatest reshuffle.

Bucket Brigade

If you are indispensable, you’re unpromotable. – Unknown

I don’t know who said that quote, but it’s pretty true, no? Some people and groups, especially bureaucrats and those in overhead middle management and staff roles, either wittingly or unwittingly do everything they can to make their jobs so complicated and unfathomable that no one else can do them and the org that employs them would be temporarily hosed if they left. It’s the familiar “truck number of 1” syndrome.

The problem is that both managers and “regular” employees in unenlightened borgs collude to make it so. Managers want efficiency to keep operating costs low and employees want a comfort zone that minimizes the chance of them making visible mistakes. Specialization breeds specialization over time until a brittle bucket brigade of one-dimensional, highly interdependent, change-averse “parts” is set in stone.

Surpise, Suprise, Surprise

I always get a kick out of how people express great surprise when a management shakeup occurs and the old guard is sacked for the not-so-old guard. “OMG! I can’t believe so-and-so is gone“. “It’s about time so-and-so got booted“. “Why the hell is so-and-so still here?“. “Why am I still here?“.

Well geeze, the reason a change was made was because it finally became unavoidably obvious that something wasn’t working the way it should to somebody who had the power to make the change. Nonetheless, changing a leadership team in response to an existential crisis doesn’t guarantee squat. At best, the new team will propel the org out of the crisis and place it on a trajectory of success. At worst, the org’s demise will be accelerated.

What Will The Children Think?

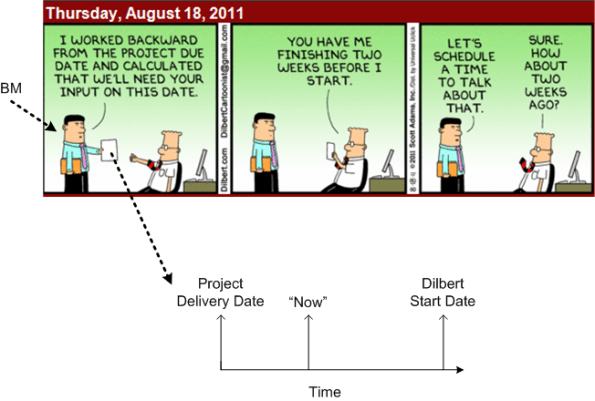

Defacement

While browsing for blog post ideas, I felt a strong need to deface this Dilbertonian classic with BD00 graffiti:

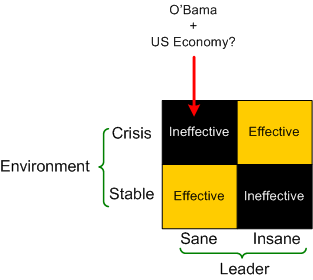

Sanity, Stability, Insanity, Instability

Because of the seemingly outrageous premises upon which the book is based, I found Nassir Ghaemi’s “A First-Rate Madness: Uncovering the Links Between Leadership and Mental Illness” fascinating. Mr. Ghaemi asserts that mentally healthy leaders do a great job in times of stability, but they fail miserably in times of crisis due to something akin to acquired “hubris syndrome“. On the flip side, he asserts that mentally unhealthy leaders, being more empathic ans less susceptible to hubris syndrome, are effective in times of crisis, but woefully ineffective in stable times.

What follows is the impressive list of leaders Mr. Ghaemi “analyzes” to promote his view. First, the wackos: William Tecumseh Sherman, Ted Turner, Winston Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy. Next, the sane dudes: Richard Nixon, George McClellan, Neville Chamberlain, George W. Bush, and Tony Blair. He also “delicately” addresses where Adolph Hitler fits into his scheme of things.

Here are several passages that I highlighted on my Kindle and shared on Twitter:

We are left with a dilemma. Mental health—sanity—does not ensure good leadership; in fact, it often entails the reverse. Mental illness can produce great leaders, but if the illness is too severe, or treated with the wrong drugs, it produces failure or, sometimes, evil. The relationship between mental illness and leadership turns out to be quite complex, but it certainly isn’t consistent with the common assumption that sanity is good, and insanity bad.

Depression makes leaders more realistic and empathic, and mania makes them more creative and resilient. Depression can occur by itself, and can provide some of these benefits. When it occurs along with mania—bipolar disorder—even more leadership skills can ensue. A key aspect of mania is the liberation of one’s thought processes.

Creativity may have to do less with solving problems than with finding the right problems to solve. Creative scientists sometimes discover problems that others never realized. Their solutions aren’t as novel as is their recognition that those problems existed to begin with.

In a strong economy, the ideal business leader is the corporate type, the man who makes the trains run on time, the organizational leader. He may not be particularly creative, but he doesn’t need new ideas; he only needs to keep going what’s going. Arthur Koestler called this kind of executive the Commissar; much as a Soviet bureaucrat administers the state, the corporate executive administers the company. This is not a minor matter; administration is no easy task; but with this approach, all is well only when all that matters is administration.

When the economy is in crisis, when profits have fallen, when consumers no longer demand one’s goods or competitors produce better ones, then the Commissar fails; the corporate executive takes a backseat to the entrepreneur, whom Koestler called the Yogi. This is the crisis leader, the creative businessman who either produces new ideas that navigate the old company through changing times or, more often, produces new companies to meet changing needs.

Yet absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Like Gandhi, King tried to commit suicide as a teenager; in fact, King made two attempts. It is surprising how little this fact is recalled.

Many people fear nothing more terribly than to take a position which stands out sharply and clearly from prevailing opinion. The tendency of most is to adopt a view that is so ambiguous that it will include everything and so popular that it will include everybody. . . . The saving of our world from pending doom will come, not through the complacent adjustment of the conforming majority, but through the creative maladjustment of a nonconforming minority.

Mentally healthy leaders like George W. Bush make decisions, but refuse to modify them when they do not work well.

Still, given the challenges, some might well ask: Why take the risk? Why not just exclude the mentally ill from positions of power? As we’ve seen, such a stance would have deprived humanity of Lincoln, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Kennedy. But there’s an even more fundamental reason not to restrict leadership roles to the mentally healthy: they make bad leaders in times of crisis—just when we need good leadership most.

Most of us think and act similarly. Most people have a hard time admitting error, apologizing, changing our minds. It takes more than a typical amount of self-awareness to realize that one is wrong and to admit it.

“Proud mediocrity” resists the notion that what is common, and thus normal, may not be best.

Regardless of whether you agree with his analyses and conclusions after you’re done reading the book, I think you’ll have enjoyed the reading experience.”