Archive

Well Known And Well Practiced

It’s always instructive to reflect on project failures so that the same costly mistakes don’t get repeated in the future. But because of ego-defense, it’s difficult to step back and semi-objectively analyze one’s own mistakes. Hell, it’s hard to even acknowledge them, let alone to reflect on, and to learn from them. Learning from one’s own mistake’s is effortful, and it often hurts. It’s much easier to glean knowledge and learning from the faux pas of others.

With that in mind, let’s look at one of the “others“: Hewlitt Packard. HP’s 2010 $1.2B purchase of Palm Inc. to seize control of its crown jewel WebOS mobile operating system turned out to be a huge technical and financial and social debacle. As chronicled in this New York Times article, “H.P.’s TouchPad, Some Say, Was Built on Flawed Software“, here are some of the reasons given (by a sampling of inside sources) for the biggest technology flop of 2011:

- The attempted productization of cutting edge, but immature (freeze ups, random reboots) and slooow technology (WebKit).

- Underestimation of the effort to fix the known technical problems with the OS.

- The failure to get 3rd party application developers (surrogate customers) excited about the OS.

- The failure to build a holistic platform infused with conceptual integrity (lack of a benevolent dictator or unapologetic aristocrat).

- The loss of talent in the acquisition and the imposition of the wrong people in the wrong positions.

Hmm, on second thought, maybe there is nothing much to learn here. These failure factors have been known and publicized for decades, yet they continue to be well practiced across the software-intensive systems industry.

Obviously, people don’t embark on ambitious software development projects in order to fail downstream. It’s just that even while performing continuous due diligence during the effort, it’s still extremely hard to detect these interdependent project killers until it’s too late to nip them in the bud. Adding salt to the wound, history has inarguably and repeatedly shown that in most orgs, those who actually do detect and report these types of problematiques are either ignored (the boy who cried wolf syndrome) or ostracized into submission (the threat of excommunication syndrome). Note that several sources in the HP article wanted to “remain anonymous“.

Related articles

- Sluggish code and HP power plays blamed for webOS’ failure (slashgear.com)

- Leaks: webOS struggled with poor staff, fundamental design (electronista.com)

- Why WebOS Failed (technologizer.com)

Fish On Fridays

Note: Today, on 12/23/11, I’m delighted to present to you the first guest blog entry ever posted on bulldozer00.com. Woot! The following delicious blarticle comes to you from a frequent BD00 blog commenter who logs on using a myriad of creative names with the word “fish” in them. Could it be Abe Vigoda in disguise?

————————————————————————————————————–

Seasons Greetings to the followers of BD00’s blog—Welcome to a not-so-periodic, occasional feature we’re going to call “Fish on Fridays“.

Everyone knows the Bulldozer here puts in a great deal of effort spinning his wheels and blogging about the world as he sees it. And like everyone, he deserves a break–a vacation if you will. So here I am pinch-hitting every once in a while so BD00 can enjoy that extra dirty martini over the holidays.

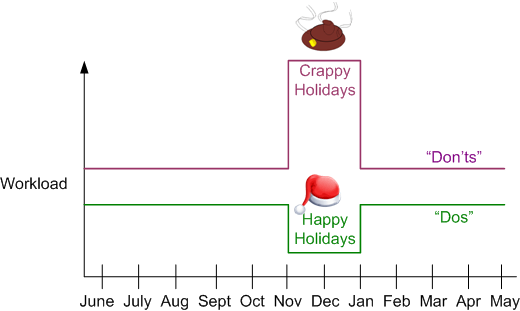

Yesterday’s blog about glorifying the Salesmen and the Accountants spelling the demise of a company got me thinking about the perceptions of the people that “Do” versus the people that “Don’t“.

I’m a creative–not a code jockey like the ‘dozer. I take blank sheets of paper (white-screen on a monitor these days) and I draw up conceptual design solutions to merchandise consumer products in appealing ways and dress up retail environments that will convince consumers to part with their hard-earned cash for that next great thing in the store.

This time of year, there’s always a huge battle that goes on at just about every company, where the people that “Do” decide to take time off from their work and take a well-deserved vacation; a break from the daily grind. This leaves the people who “Don’t” holding the reigns while those that “Do” are away. In my company, two things happen. The people that “Do” (salesmen) all rush in with a whole list of new projects that require the people that “Don’t” to generate a great deal of output while those that “Do” are away. Generally, this output has a well-defined deadline–the “First of the Year” or “Right after the Holiday“, or “As soon as we get back“. This allows them to set up a huge flurry of new customer visits and get a ‘fresh start‘ on the year, while they take their break and kick up their feet in the sand with a cooler of Corona’s beside them.

As a result, the people that “Do” go away for a week or two, and the people that “Don’t” have a mad rush of activity that must all be completed right at the time when EVERYONE wants to take a break and enjoy the season. Usually, this also means short-time frames as there are at least 2 and sometimes 3 or 4 workdays that have been turned into corporate days off, so the actual work-week is truncated and those that “Don’t” actually have much less time to complete their tasks than they normally would. This is compounded by the fact that at least a portion of the people that “Don’t” are also taking time off, leaving a skeleton crew around to cover and handle the work that comes in.

Quite often, particularly when your business activities rely on the support of other businesses (suppliers, contractors, agencies, etc), everything at this time of year slows down or becomes impossible because everyone is short-handed. You can’t get answers from your customer, the salesperson is unavailable to help, you can’t find stuff, and the outside groups you depend on are unable to respond in the same timely manner as you are used to. As a result, the things you need to do can’t get finished until everyone else gets back and you get to start the year with a whole bunch of extra time in the office, sweating out the details while those who “Do” are off relaxing.

The perception is that there is this great holiday season and everyone should enjoy it, but in the great corporate world of BOZOs the reality is that there is usually one class of workers where the holiday time is one of the busiest and most stressful times of the year. I found this quote from an Apple employee that just about sums it all up…

You can expect that your needs will always come second to “the needs of the business”. In fact, anytime you hear that phrase, be prepared for the next sentence to describe how you’re going to be screwed. For example, “I’m sorry, Joe, but the needs of the business dictate that you can’t take a vacation between October and February, or June through September”.

I am reminded of the movie Ants, where the worker Ants–those that ‘Don’t‘ bust their little exoskeletons to feed the Grasshoppers who ‘Do‘. There is a quote in this blog attributed to Tom Sutcliffe where he is looking at the recent uprisings in Egypt and comparing them to business. Sutcliffe mentions that:

It seems odd that people will endure, within the framework of a firm or an institution, a degree of subjection and speechlessness that would strike them as insufferable at the level of citizenship and that “office tyrannies” might end up becoming the target of mass uprisings not unlike those that we have been witnessing in the Middle East.

At a forward thinking company, the entire place shuts down for the holidays–no one is left holding the bag. But with the glorification of those that ‘Do‘ as BD00 discussed, we are creating an internal separation between groups, which is part of the process of demise. Look at your company and the people around you. Are you someone that “does” or someone that “doesn’t“? What are you doing for the people on the other side of that equation?

Happy Holidays?

Baggage From The Past

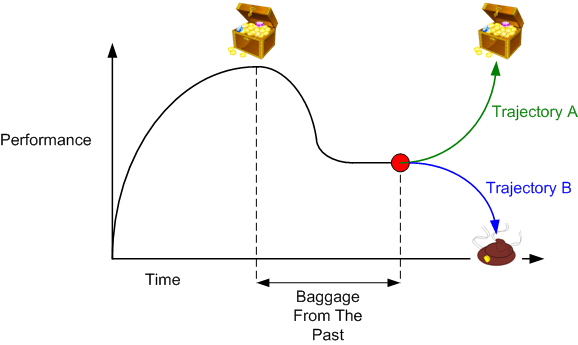

BD00, the wise ass, oops, I mean the wise child that he is, maintains that it’s much more challenging to restore a fallen org to success than it is to bootstrap a startup org to success.

Unlike established orgs, startups are populated by a small group of highly enthused people with a common bond and they don’t have a history of under performance to contend with (yet) as they move forward.

It’s BD00’s belief that leadership teams who turn around fallen stars are more deserving of kudos than heroic startup teams.

It’s BD00’s belief that leadership teams who turn around fallen stars are more deserving of kudos than heroic startup teams.

Cribs And Complaints

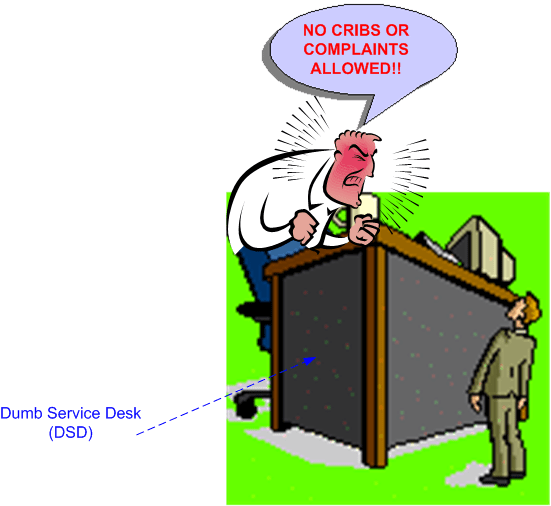

HCL Technologies CEO Vineet Nayar‘s “Employees First, Customers Second” is one of the most refreshing business books I’ve read in awhile. One of the bold measures the HCLT leadership team considered implementing to meet their goal of “increasing trust through transparency” was to put up an intranet web site called “U & I“. After weighing the pros and (considerable) cons, the HCLT leadership team decided to go for it. Sure enough, the naysayers (Vineet calls naysayers the “Yes, But“s) were right:

The U&I site was clogged with cribs and complaints, harangues and imprecations that the company was wrong about everything. The continents and questions came pouring in and would not stop. Most of what people said was true. Much of it hurt.

However, instead of placing draconian constraints on the type of inputs “allowed“, arbitrarily picking and choosing which questions to answer, or taking the site down, Vineet et al stuck with it and reaped the benefits of throwing themselves into the fire. Here’s one example of a tough question that triggered an insight in the leadership team:

“Why must we spend so much time doing tasks required by the enabling functions? Shouldn’t human resources be supporting me, so I can support customers better? They seem to have an inordinate amount of power, considering the value they add to the customer.”

This question suggested that organizational power should be proportionate to one’s ability to add value, rather than by one’s position on the pyramid. We found that the employees in the value zone were as accountable to finance, human resources, training and development, quality, administration, and other enabling functions as they were to their immediate managers. Although these functions were supposed to be supporting the employees in the value zone, the reality was sometimes different.

That question led to the formation of the Smart Service Desk (SSD), which helped the company improve its operations, morale, and financial performance.

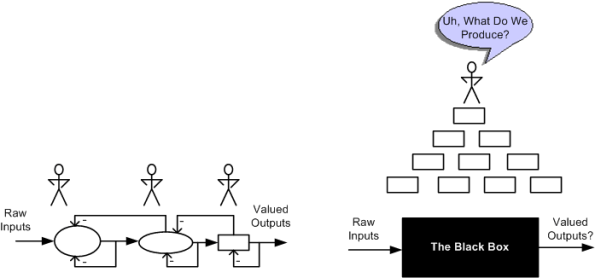

So, how did the SSD work, you ask? It worked like this: SSD. Not like this:

Apple-less

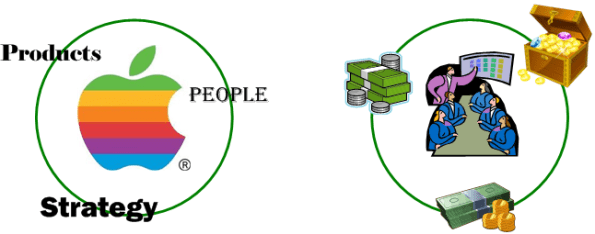

Amazingly, I’ve never owned an Apple product. Despite this fact, I admire Apple and the culture that Steve Jobs brutally, but single-handedly, instilled into the company. These excerpts from “Jobs questioned authority all his life” explain why:

Jobs called the crop of executives brought in to run Apple after his ouster in 1985 “corrupt people” with “corrupt values” who cared only about making money. Jobs himself is described as caring far more about product than profit.

He told (biographer) Isaacson they cared only about making money “for themselves mainly, and also for Apple — rather than making great products.”

Despite Apple’s unprecedented success behind Jobs’ “products, strategy, people” credo, most captains of industry and their mini-me clones just don’t get it – and it looks like they never will. I think capitalism is the least inequitable “ism” there is, but extreme capitalism is no better than any other “ism“.

Sustained Viability

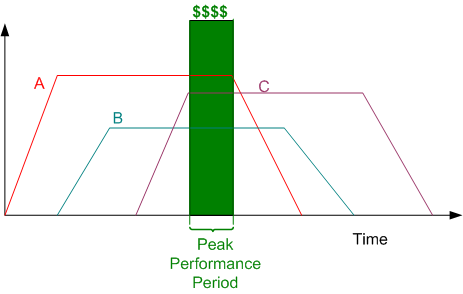

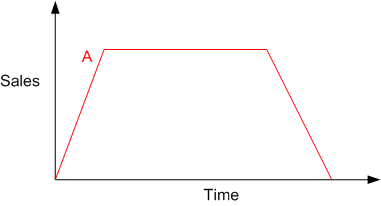

The figure below shows the sales-vs-time trend chart of a one hit wonder company. The sales from product “A” ramp up, settle out, and then ramp down.

The ramp up, steady-state, and ramp down time intervals in which sales > $0 varies wildly from one company to another and depends on many factors: how easy the product is to copy, whether the product is obsoleted by another product, how big the market is, whether or not the product keeps evolving to meet new customer demands; yada, yada, yada.

The ramp up, steady-state, and ramp down time intervals in which sales > $0 varies wildly from one company to another and depends on many factors: how easy the product is to copy, whether the product is obsoleted by another product, how big the market is, whether or not the product keeps evolving to meet new customer demands; yada, yada, yada.

To maintain sustained viability and to avoid being a one hit wonder company, new products must be continuously developed to offset the eventual decline in sales from the aging one hitter. The longer the “flat” segment of sustained sales is, the easier it is to become fat/happy/complacent and stop creating and innovating.

The figure below traces the rise and fall of a three hit company. The green vertical lines are snapshots of the company’s sales at four different points in time.

At the peak of success, all three products have leveled off at their maximum sales levels and the good times are a rollin’. Then, for an unknown reason(s), the product pipeline is suddenly empty, and one by one, sales start decreasing for each product.

So what’s the point of this inane post? Hell, I don’t freakin’ know. I was just doodlin’ around with visio, sketchin’ away, makin’ stuff up, and these graphs emerged from the wild blue yonder. Sorry for wastin’ your time. It wasn’t a waste of mine.

Exactly Two Years Hence

Before going any further, make a note of today’s date. Now, if you want to follow the timeline of a sad story, then perform the following procedure while noting the date of each post:

1 Read this post: My Company

2 Then read this post: The End Of An Era

3 Then read this post: Heartbroken, But Hopeful

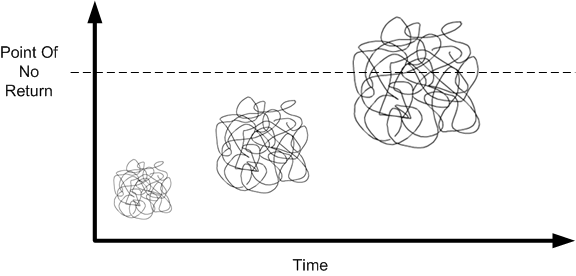

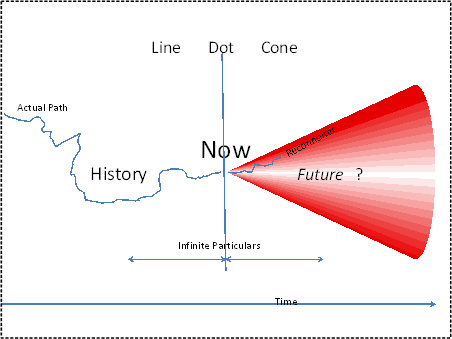

So, what does the future hold? Hell, I don’t freakin’ know. My friend Bill Livingston‘s line-dot-cone sketch says it all:

Miraculous Recovery

It’s a miracle, a true blue spectacle, a miracle come true – Barry Manilow

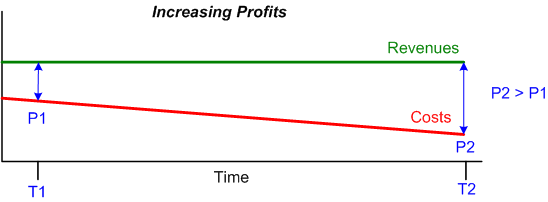

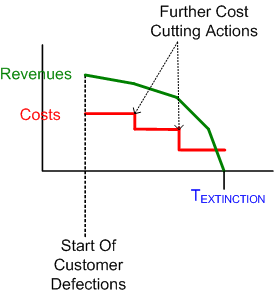

The business equation is as simple as can be: profits = revenues – costs. For the moment, assume that increasing revenues is not in the cards. Thus, as the graph below shows, the only way of increasing profits is to reduce costs.

By far, the quickest, most efficient, and least challenging method of reducing costs is by shrinking the org. However, the well known unintended consequences of reducing costs by jettisoning people are:

- increased workload on those producers “lucky enough” to remain

- the loss of bottom up trust and loyalty,

- lowered morale, increased apathy and skepticism

- less engagement, lowered productivity

- the loss of even more good people seeking out a better future

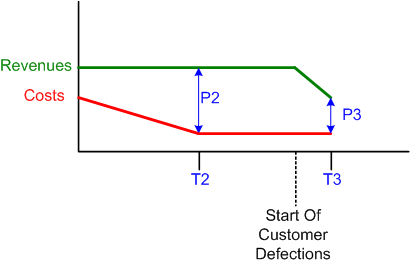

Unless these not-so-visible unintended consequences are compensated for (which they usually aren’t), the increase in profits may be short-lived. Sometime later, revenues may start decreasing as a result of customer defections triggered by deteriorating product and service quality.

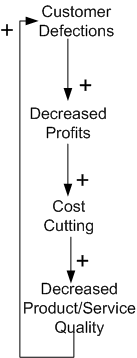

As the system dynamics influence diagram below shows, the start of customer defections may trigger a vicious downward spiral into oblivion in the form of a positive feedback loop. An increase in customer defections leads to an acceleration in the decrease in profits, which leads to an increase in cost cutting measures, which accelerates decreased product/service quality, which increases the number of customer defections.

Once the vicious cycle commences, unless the loop is broken somehow, the extinction of the org and all of its “innards” is a forgone conclusion:

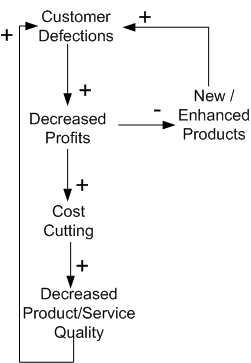

So, how can the cycle be broken? Well duh, by increasing revenues. So, how can revenues be increased? By somehow “miraculously”:

- Creating new products/services that customers want and competitors don’t have yet

- Enhancing the existing product/service portfolio to distinguish the org’s offerings from the moo herd’s crappy products/services

But wait, you say. How can an org enhance their products and/or create new ones with no capital to invest because of decreasing (or no) profits? Then, uh, that’s where the “miraculously” comes in.

In a tough business environment, it doesn’t take much to cut costs (that’s what dime-a-dozen MBAs and mercenary hatchet men are for). It takes talent, ingenuity, lots of luck, and real leadership to increase revenues when little to no investment resources are available. No matter how sincere, text book exhortations, rah rah speeches, and appeals for increased focus/dedication/loyalty (with no reciprocating commitment for compensation should the ship be righted), aren’t characteristic of real leadership. They’re manifestations of fear.

Borgbot

I’m not sure you should worry much about the effect your behavior has on the organization overall, because there’s lots of data that suggests the organization doesn’t care much about you. – Jeffrey Pfeffer

That quote by Stanford University’s Jeffrey Pfeffer can be found in The Purpose of Power. From one systems point of view, a corpricracy as a whole is an inflexible and conscienceless borgbot with a single purpose – to make as much money it can, in any way it can. If the borgbot needs to chop off its nose or sell its mother into slavery or bankrupt millions of people outside its walls to fulfill its mission, it will.

The fascinating thing about borgbot behavior is that it ingeniously guilts its members into compliance (“aren’t you a team player?“, “if you don’t do it, you’re selfish and you’ll hurt the company“, “how dare you question management decisions“, “you’re a disloyal ingrate for speaking out“, yada-yada-yada) and rationalizes any unethical behavior away without blinking an eye.

Like most of us, Pfeffer wishes large-scale organizations were paragons of meritocracy where competence and influence are always perfectly correlated, but he knows that’s not the case – Gary Hamel

Notice the usage of the term “large-scale organizations” in Mr. Hamel’s quote. It implies that there’s hope – in small scale organizations. It makes self-righteous BD00 wonder why borgbots are obsessed with growth. Oh, I almost forgot; to make as much money as they can in any way they can.

Fuzzy And Clear

The higher one ascends up the corpo ladder, the fuzzier one’s view becomes regarding how the enterprise works and what mania takes place down in the boiler rooms. On the other hand, who reports to whom becomes clearer and clearer and perversely more important than nurturing continuous improvement and innovation. These effects can be called “losing touch with reality” and “perverse inversion of importance“.