Archive

Generating NaNs

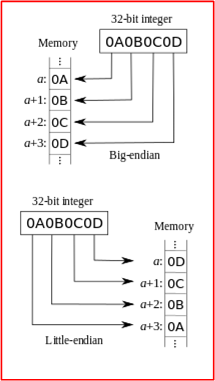

While converting serialized double precision floating point numbers received in a datagram over a UDP socket into a native C++ double type, I kept getting NaN values (Not a Number) whenever I used the deserialized version of the number in a numeric computation. Of course, the problem turned out to be the well-known “Endian” issue where one machine represents numbers internally in Big Endian format and the other uses Little Endian format.

One way of creating a NaN is by taking the square root of a negative number. Another way is to jumble up the bytes in a float or double such that an illegal bit pattern is produced. Uncompensated Endian mismatches between machines can easily produce illegal bit patterns that create NaNs. Note that NaNs are only an issue in the floating point types because every conceivable bit pattern stored in an integral type is always legal.

To prove just how easy it is to produce a NaN by jumbling up the bytes in a double, I wrote this little program that I’d like to share:

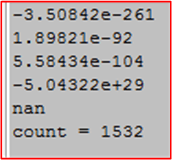

Here is a fragment of the output from a typical program run:

I was a little surprised at the low number of iterations it typically takes to produce a NaN, but that’s a good thing. If it takes millions of iterations, it may be hard to trace a bug back to a NaN problem.

For those who would try this program out, here is a copy-paste version of the code:

#include <cstdint>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

#include <cmath>

int main() {

//Determine the number of bytes in a double

const int32_t numBytesInDouble{sizeof(double)};

//Create a fixed-size buffer that holds the number of bytes

//in a double

int8_t buffer[numBytesInDouble];

//Setup a random number generator to produce

//a uniformly distributed int8_t value

std::random_device rd{};

std::mt19937 gen{rd()};

std::uniform_int_distribution<int8_t> dis{-128, 127};

//interpret the buffer as a double*

const double* dp{reinterpret_cast<double*>(buffer)};

int32_t count{-1};

do{

//fill our buffer with random valued bytes

for(int32_t i=0; i<numBytesInDouble; ++i) {

buffer[i] = dis(gen);

}

std::cout << *dp << "\n";

++count;

}while(not std::isnan(*dp));

std::cout << "count = " << count << "\n";

}

Perfect And Real

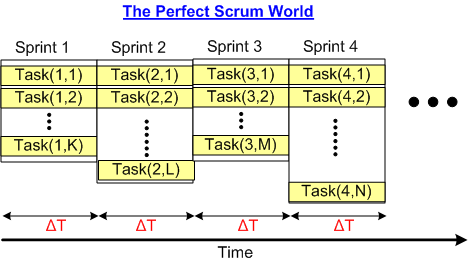

In the perfect Scrum world, software is developed over time in fixed-size (ΔT) time boxes where all the work planned for the sprint is completed within the timebox. Typically ΔT is chosen to be 2 or 4 weeks.

If all the tasks allocated to a sprint during the planning meeting are accurately estimated (which never happens), and all the tasks are independent (which never happens), and any developer can perform any task at the same efficiency as any other developer (which never happens), then bingo – we have a perfect Scrum world.

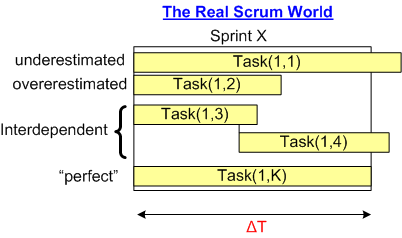

However, in the real world (Scrum or non-Scrum), some (most?) tasks are interdependent, some tasks are underestimated, and some tasks are overestimated:

Thus, specifying a fixed ΔT timebox size for every single sprint throughout the effort may not be a wise decision. Or is it?